For the second afternoon in a row, a potent cold front has swept across Denver, marking the return of a deep freeze for much of the country. Yesterday, my weather station recorded a 32-degree drop in less than 90 minutes (here’s a chart).

This latest cold snap is sure to revive talk about the polar vortex, a persistent upper-level cyclone that swirls high above the Arctic and Antarctica, so I thought I’d round up some visualizations that illustrate what’s happening.

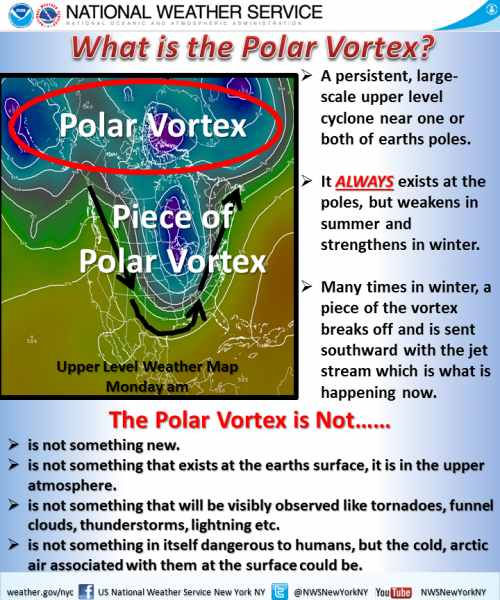

The graphic below, from the National Weather Service, explains what the polar vortex is, and isn’t.

The polar vortex always remains above the poles, but sometimes the Arctic vortex weakens and allows some frigid air to move south into the United States. (CNN has a good piece explaining why the polar vortex is something of a misnomer for describing the weather we’re experiencing in the states.)

NASA has also produced a great little video describing how the polar vortex works:

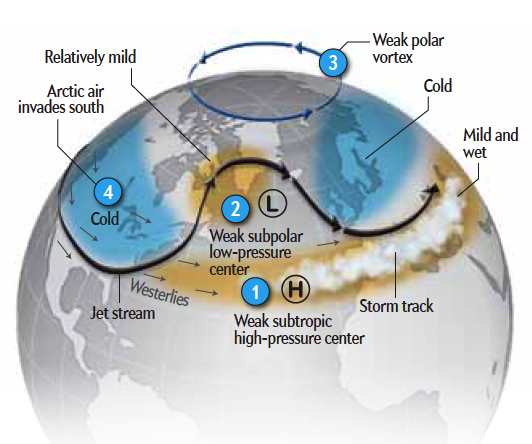

Here’s a graphic from the CBC up in Canada, where they have even more experience with the polar vortex.

I also found the graphic below from Scientific American to be helpful in understanding the concept.

Although the polar vortex has been portrayed by some as disproving global warming, there is actually evidence that climate change is playing some role in the cold air descending south. The thinking is that warming in the Arctic is messing with the vortex and associated jet stream. Brian Walsh has a nice summary in Time and Eric Holthaus has a good explainer at Quartz.

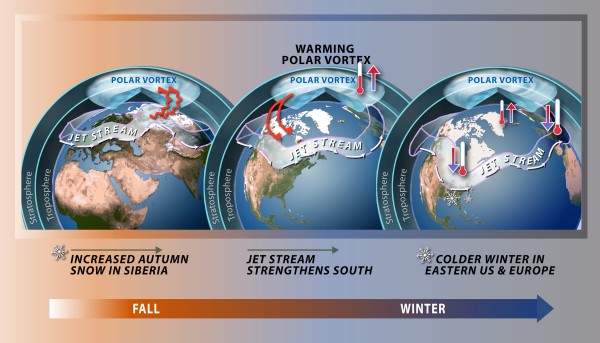

There’s also some research linking heavy autumn snows in Siberia to the polar vortex and abnormally cold weather in the Eastern United States and Europe, according to an NSF-funded study.

Here’s how NSF describes the graphic above:

Researchers have validated a new weather prediction model that uses autumn snowfall to predict winter cold in the United States and Europe. When snowfall is high in Siberia, the resultant cold air enhances atmospheric disturbances, which propagate into the upper level of the atmosphere, or stratosphere, warming the polar vortex. When the polar vortex warms, the jet stream is pushed south leading to colder winters across the eastern United States and Europe. Conversely, under these conditions the Arctic will have a warmer than average winter.

It’s amazing how the snowpack in Siberia can affect the temperature in New York, and it almost sounds like an example of the butterfly effect, the notion coined by chaos theory pioneer Edward Lorenz that small perturbations in a system can theoretically have large effects down the line (e.g., a butterfly flapping its wings causing a hurricane halfway around the globe).

Just as fascinating to me is how the term “polar vortex” has roared onto the scene this winter like an Arctic cold front sweeping down the High Plains. I’m something of a weather nerd, but I hadn’t heard much about the polar vortex before it caught hold during the January cold snap.

But this is not some newfangled scientific concept. The term was used as early as 1853, and the apparent trigger for the cold wave in early 2014, a phenomenon called sudden stratospheric warming, was discovered in 1952. Rush Limbaugh claimed that the polar vortex was a “hoax” created by the liberal media. NBC weatherman Al Roker set the record straight with a tweet:

For all the doubters who say the media “created” the Polar Vortex: From the 1959 AMS Glossary of Meteorology pic.twitter.com/x2Nyw0jx3j

— Al Roker (@alroker) January 7, 2014

I’d love to see an analysis of how this term took hold and was used/misused as a case study in science communications and journalism. The word “vortex” has a certain mystical quality; for me, it instantly conjures Sedona, where supposed vortices of spiritual energy are located among the red rock formations. If you ask Google to define vortex, the second definition, after the physics stuff, is “something regarded as a whirling mass” with the example of “the vortex of existence.” So perhaps vortex captures the American zeitgeist.

According to Wikipedia, the polar vortex is also known both as the “polar low,” which sounds to me like a term a psychiatrist would use to describe a depressed patient, and “circumpolar whirl,” which makes me think of a dance step or frosted decoration on a cake. I wouldn’t expect to see “polar low” or “circumpolar whirl” getting as much ink or scrolling on cable news.

Whatever the reason, the polar vortex has entered the American consciousness, and the exceptionally cold temperatures in some of the country for a portion of the winter have become part of the whole climate change narrative. It takes some mental jujitsu to yield to the counter-intuitive notion that global warming can actually cause cold waves to plunge deeper and increase the frequency of epic snow storms while also threatening the snowpack overall.

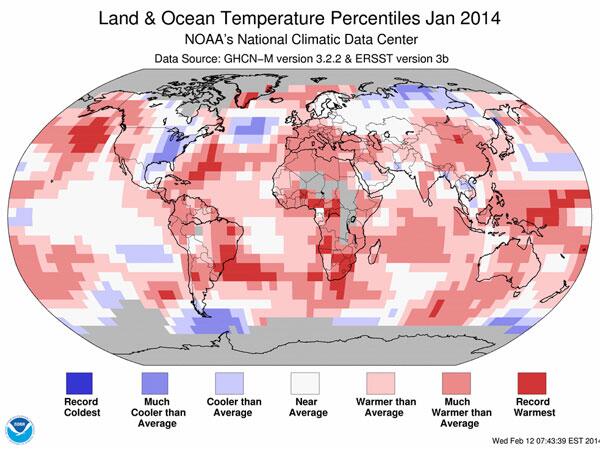

For all the talk of Arctic air masses in the states, January was the fourth-warmest year on record for the globe, as shown in the NOAA map below, so it’s important to remember that a piece of the polar vortex is influencing a temporary weather pattern on just one portion of the planet.

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.