Governments around the world protect places for a variety of reasons. There are landscapes set aside for critters and memorials to fallen warriors. In the United States and elsewhere, one of the biggest motivations for creating national parks and other preserves is that they’re pretty to look at and photograph.

Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but aesthetics and scenic vistas also figure prominently in things like environmental impact statements. Is there a way to quantify how photogenic or beautiful a spot is?

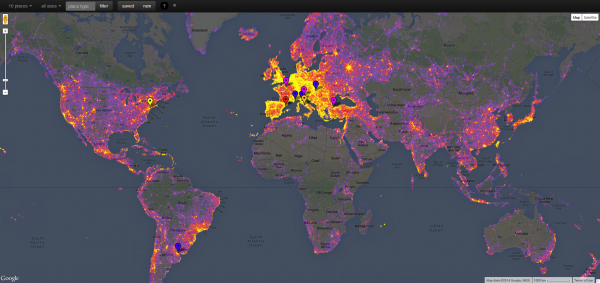

Sightsmap is the closest thing I’ve found. Using data from photos uploaded and geotagged in Panoramio, a popular photo sharing service acquired by Google in 2007, Sightsmap generates high-resolution heat maps that illustrate the number of photos snapped at sites around the world. Below are global and U.S. maps (click to enlarge, and see this gallery for more maps).

Panoramio already has more than 100,000,000 images, but its photos represent just a tiny fraction of the millions of images captured every day on Earth. Data from Panoramio’s sample isn’t representative. Among other biases, the service appears particularly popular in Europe, and there are data quality issues I note below. Despite these limitations, Sightsmap tells some interesting stories about how we travel and photograph the world around us.

Some popular unpopulated places

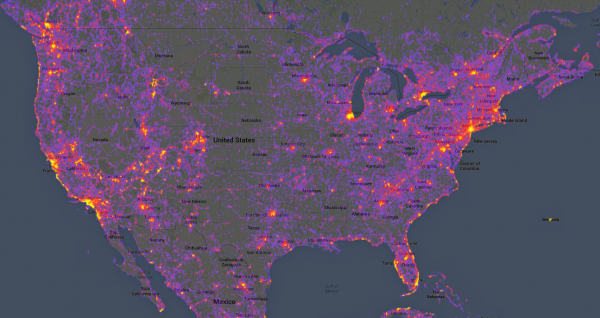

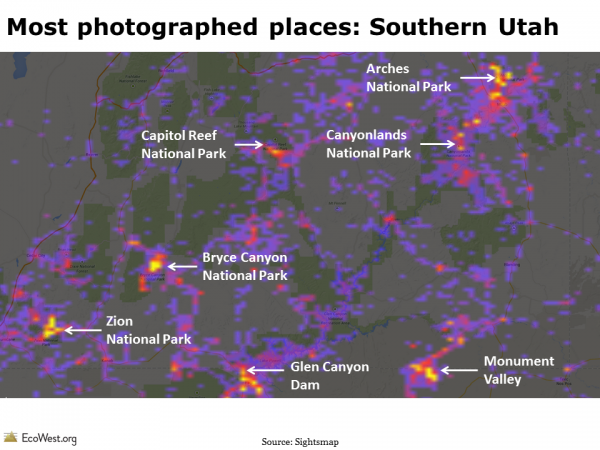

As you would expect, more populated places tend to have more photographs on Sightsmap, but there are plenty of hotspots in unpopulated parts of the American West (and other regions). The map below shows that Southern Utah, one of the least populated places in the continental United States, is also one of the most photographed because it’s home to so many national parks and tourist attractions.

Sightsmap allows you to drill down and show the density of photographs at a very high resolution. Once you’re zoomed in close enough, you can also see thumbnails of the images. Below is the heat map for the area around Delicate Arch, in Arches National Park, plus a photo of me in that spot.

Sightsmap allows you to drill down and show the density of photographs at a very high resolution. Once you’re zoomed in close enough, you can also see thumbnails of the images. Below is the heat map for the area around Delicate Arch, in Arches National Park, plus a photo of me in that spot.

National parks: most visitors stick to roads

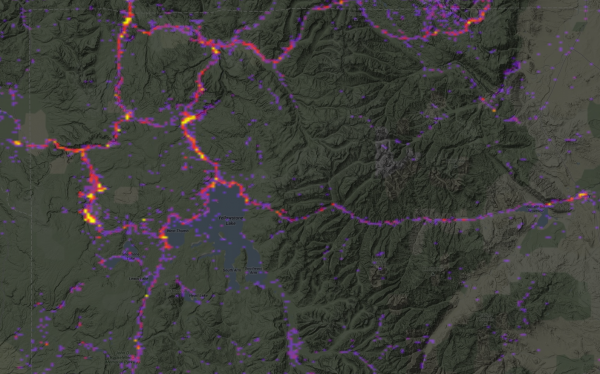

Look at the photo heat maps for national parks and you’ll see a pattern familiar to any ranger or frequent visitor: people tend to stick to the roads and pavement. Below is the Sightsmap for Yellowstone National Park.

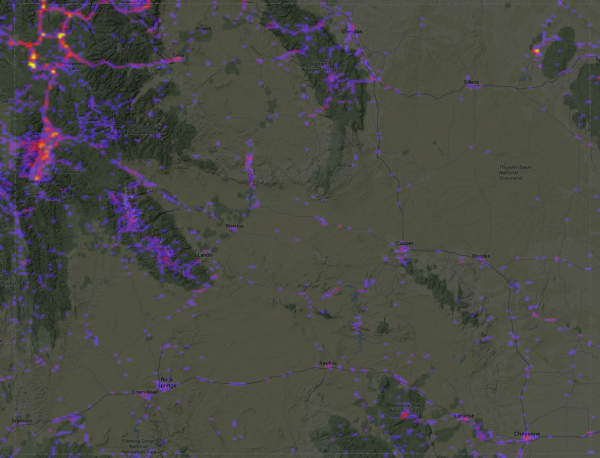

Tourists and photographers also tend to concentrate in just a few parts of Western states and cities. Below is a map of the state of Wyoming. Virtually all of the activity on Sightsmap is focused in the northwest portion of the state, home to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. Other hotspots are the Wind River Range and the Bighorn Mountains (where I photographed the sunset that appears in the EcoWest banner).

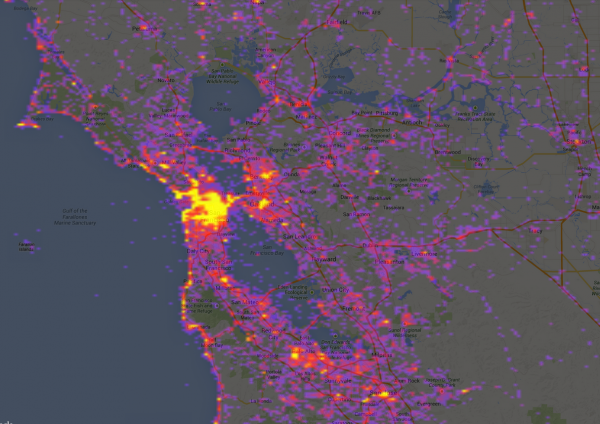

Even in a tourist mecca like the San Francisco Bay Area, where I suspect there are plenty of residents geotagging/uploading their photos, the heat maps show that certain areas are much more photogenic than others. A closeup of the 49-square-mile city of San Francisco reveals hotspots around sites such as the Golden Gate Bridge and Transamerica Pyramid, plus a fair number of shots taken on San Francisco Bay, but relatively few photos in the city’s western neighborhoods.

Restricted access: blank spots on the map

When I created human footprint maps, I was especially interested in the blank spaces where impacts were minimal. Likewise, I was instantly drawn to areas on Sightsmap where few or no photographs had been posted.

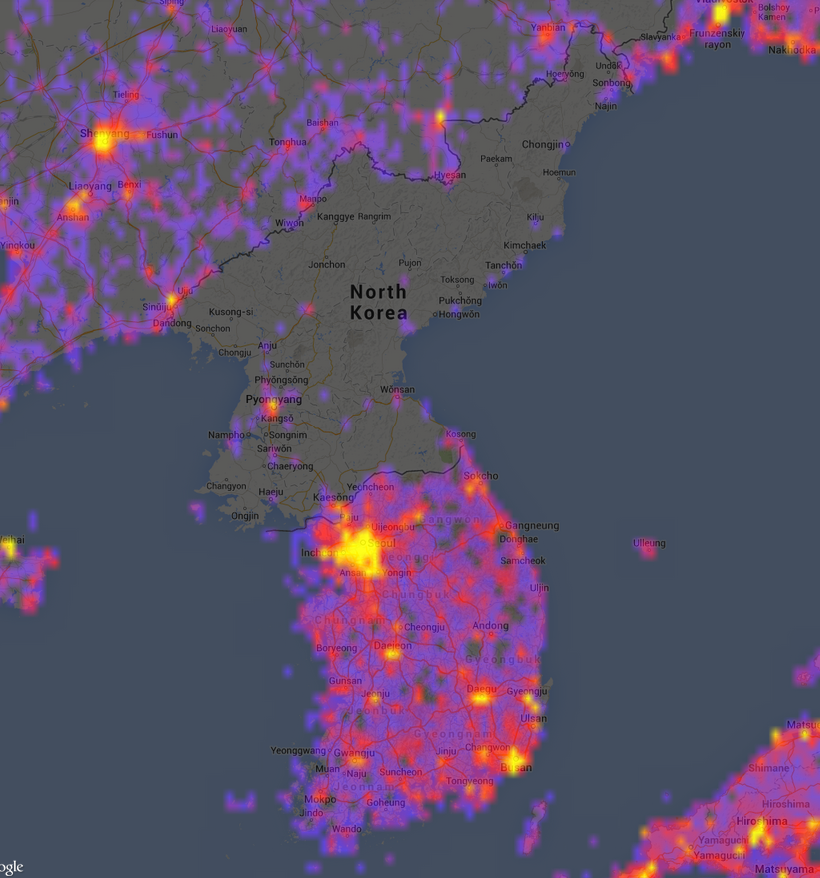

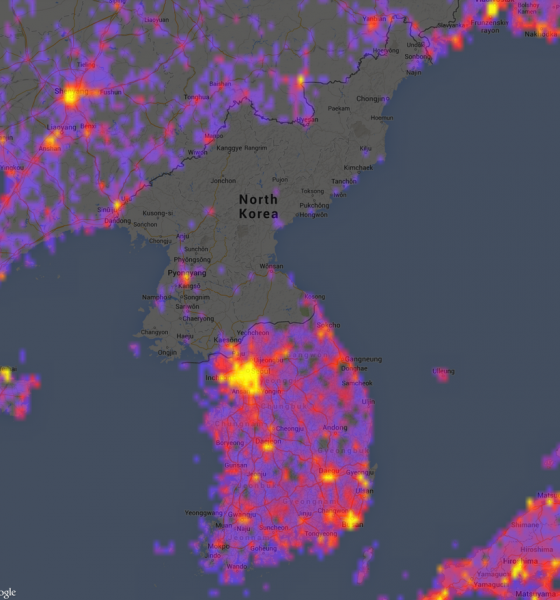

Below are two maps of the Korean Peninsula: I created the first using Sightsmap; the second was snapped by an astronaut aboard the International Space Station.

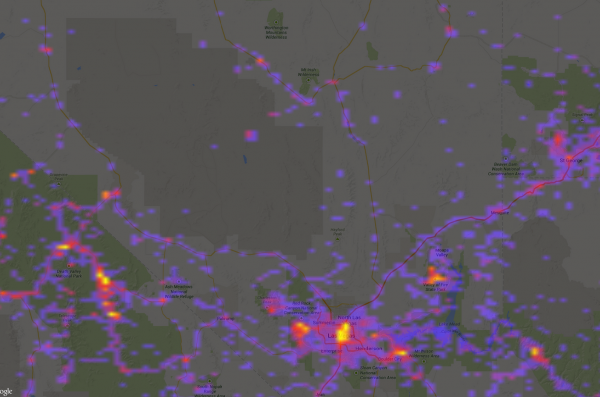

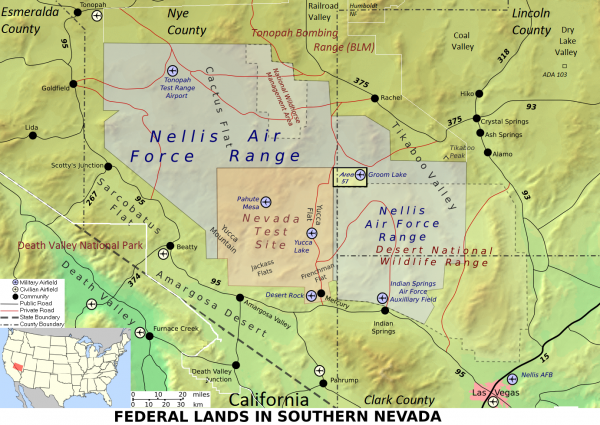

It’s easy to pick on North Korea, but we also have plenty of places in our own country where public access is prohibited. Below is a Sightsmap view of the area around Las Vegas, which includes a number of military installations to the northwest of the city that are annotated in the second map.

I was curious if there were photos of the fabled Area 51, the military installation that is ground zero for UFO folklore and assorted conspiracy theories. Sightsmap shows some grainy images of the facility that legitimately look like they were captured by photographers zooming in from surrounding mountains, plus some photos that appear to be from a tour. But there’s also this garbage image below, which someone uploaded and geotagged at Area 51, so Sightsmap surely has some questionable data.

Like any crowdsourced endeavor, Sightsmap is only as good as the data that users share and tag. Despite its flaws, I found these heat maps fascinating to explore. I could imagine them being useful not only to photographers who are plotting where to set up their tripods, but also to city planners and land managers trying to understand patterns in visitor use.

Data sources

Here’s a description from Sightsmap:

The heatmap shows the places people like, based on the number of panoramio photos at each place in the world. The dark areas have few photos, the red areas have more and the yellow areas have a large number of photos geotagged. The hottest places have markers linking photos, Streetview, Wikipedia, Wikivoyage, Foursquare and Google Plus articles about the site. The place names are selected by the Wikipedia readership numbers and foursquare checkins. Area populations are based on the geonames database. Street level heatmaps are available for [the] top 15,000 places in the world, sorted by the number of photos in an area of a size of a few square kilometers around the place center. The popularity ranking of places in high-res area maps is computed by combining place hotness with popularity rankings from Wikipedia, Foursquare and real-time Google Places selection.

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.