You may quibble with how Trulia values your home, but the real estate website provides an impressive interactive map with detailed views of social and environmental variables.

In addition to offering a treasure trove of information on real estate down to the parcel level, Trulia’s mapping engine also visualizes high-resolution data on things like commute times and the risk of wildfires, flooding, and earthquakes.

Below I describe some of my favorite features and share some screenshots. This mapping tool is not without its issues, but it’s generally well-designed and easy to use.

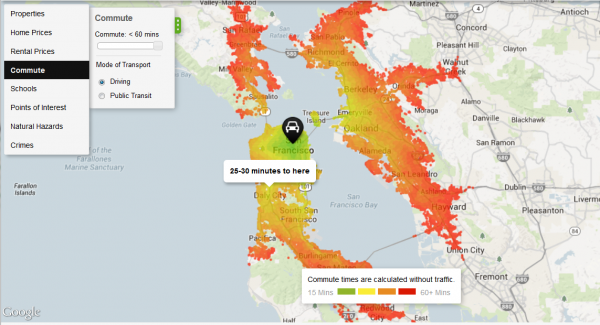

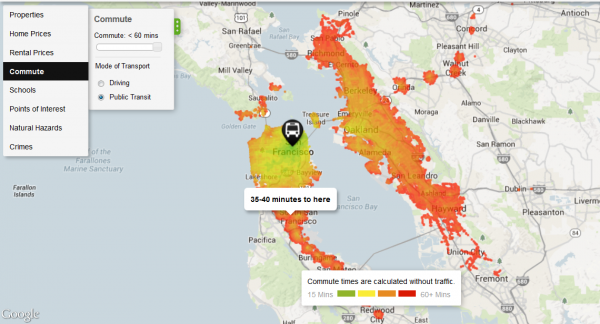

Commute times: driving and transit

One of Trulia’s most interesting features is a layer that maps commuting times. Below are the heat maps for San Francisco, first for driving and then for transit. The two maps are pretty close. Putting aside transit strikes, the Bay Area has a solid system of trains, buses, ferries, and other alternatives to driving, so commuting long distances by transit is feasible, even mandatory, for many residents in the region. These maps don’t account for traffic delays, which is a big caveat. Click on images to enlarge.

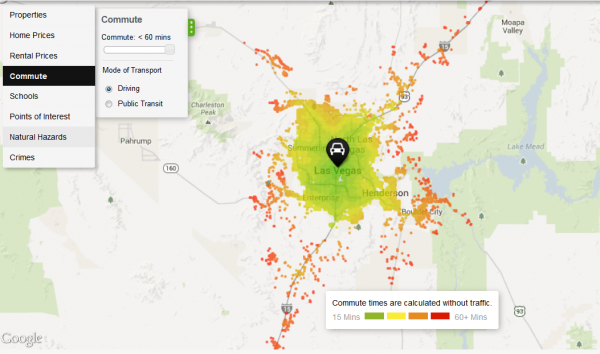

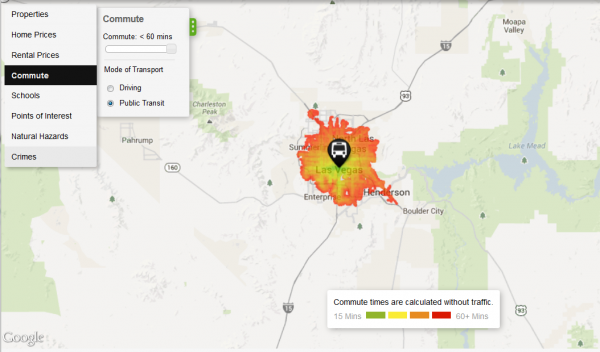

Compare the pair of images above to the ones below for Las Vegas, where there’s a huge disparity between driving and public transit commuting times. If you give yourself an hour to commute to the city center, being able to drive opens up many more places to live around Las Vegas.

Natural hazards mapped

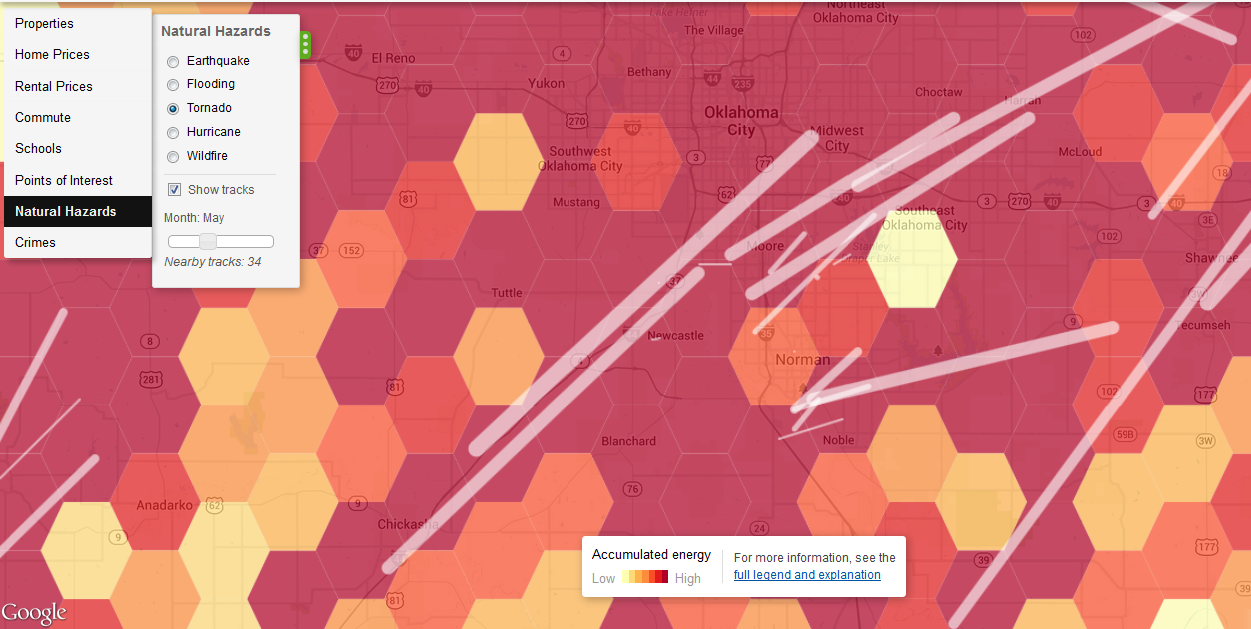

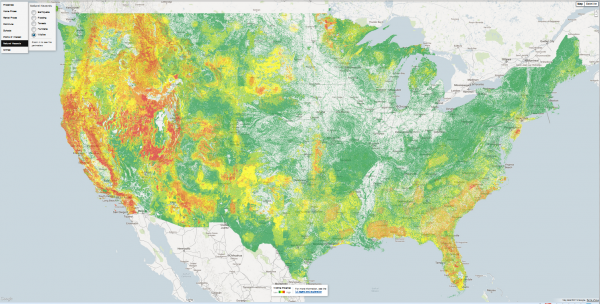

Another useful aspect of Trulia’s map is a collection of natural hazard maps, including depictions of the risks of flooding, wildfires, tornadoes, earthquakes, and hurricanes. One criticism is that the mapping engine doesn’t let you export your views, so you’ll have to rely on screenshots. It’s also difficult to zoom out and see the entire country. You can get around this by zooming out on your browser (press control and the minus sign), which is what I’ve done for the national maps below, but then the text is microscopic. Trulia works best when zoomed in to a region or metro area.

Wildfires

The map below shows wildfire potential across the country and illustrates the inherent risk of an area experiencing a severe blaze under the right conditions.

Trulia does a good job explaining its data sources. For the wildland fire potential (WFP) layer, here’s the definition they’re using:

Areas with high WFP values represent fuels with a higher probability of experiencing a high-intensity fire under conducive weather conditions. Areas with low WFP values, therefore, represent a low probability of experiencing a wildfire. The WFP map is maintained by the USDA Forest Service, Fire Modeling Institute, and is intended to be used in analyses of wildfire risk at regional or national scales. The WFP is not intended to be a forecast or wildfire outlook, as it does not include information on current or forecasted weather or fuel moisture conditions.

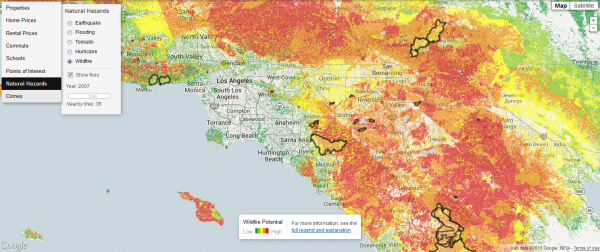

If you zoom in close enough, the wildfire data also includes perimeters of previous fires. Below is the fire potential around Los Angeles, including the outlines of fires during 2007, a particularly active year. At least in this part of the country, extremely high fire danger areas lie in close proximity to places where the risk is virtually nil.

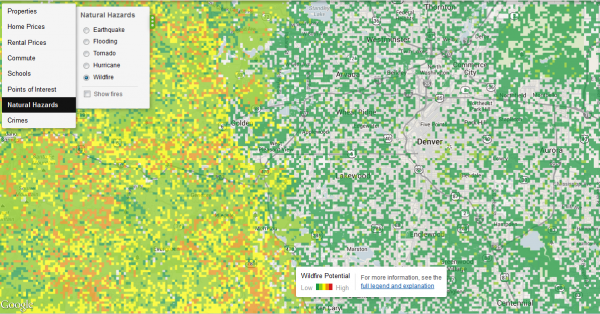

If you zoom in to some other regions, the data may get a little funky. Below is a close-up of the Denver area. In the city, the pixelated data suggests that some city blocks have a greater wildfire risk than others, but in reality you’re not going to see a wildfire within the Denver city limits. The map is basically right: as you move west, into the foothills of the Front Range, wildfire potential definitely increases, but at this resolution the map is somewhat misleading.

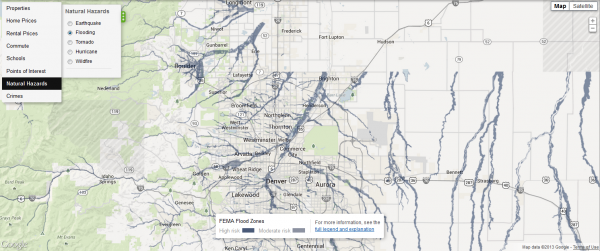

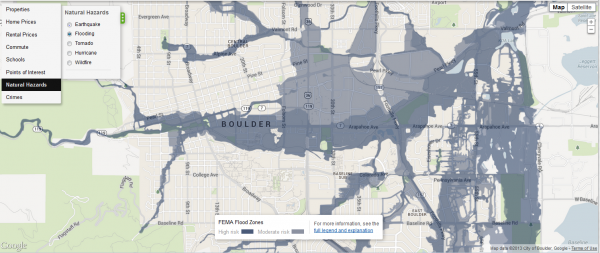

Flooding

Another limitation is that Trulia is missing data for some parts of the country. In the screenshot below, flood risks suddenly disappear north of Denver. That’s because there’s no data for Weld County. Trulia cautions that even counties with flood data from FEMA don’t necessarily have full coverage.

Here’s how Trulia describes the high (100-year flood zone ) and moderate (500-year flood zone) risk categories:

In high risk areas, there is at least a 1 in 4 chance of flooding during a 30-year mortgage. All home and business owners in these areas with mortgages from federally regulated or insured lenders are required to buy flood insurance. In moderate risk areas, the risk of being flooded is reduced but not completely removed. These areas submit over 20% of NFIP claims and receive one-third of disaster assistance for flooding. Flood insurance isn’t federally required in moderate-to-low areas, but it is recommended for all property owners and renters.

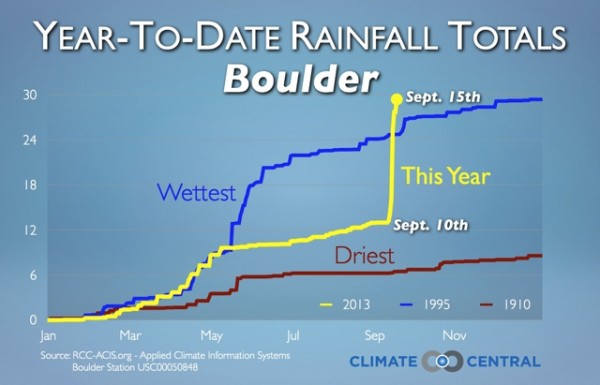

Although Trulia’s flood risk data may be spotty, covered areas are mapped in great detail, as shown in the map below of Boulder, Colorado, which recently experienced epic flooding.

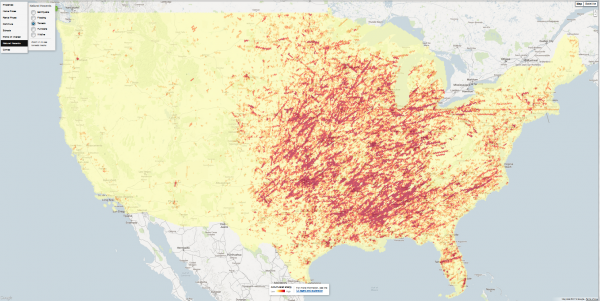

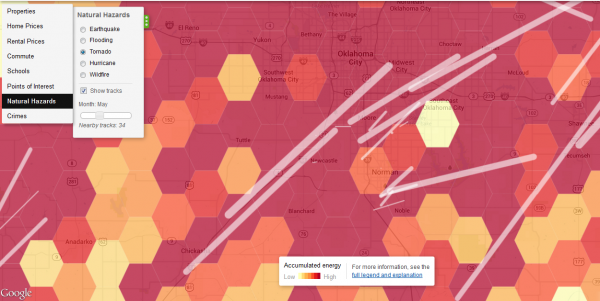

Tornadoes

Trulia’s tornado hazard map, based on data from the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center, shows that this weather phenomenon is largely absent from the American West. Drill down to the local level and the map shows the tracks of previous tornadoes. Below the national map is the area around Oklahoma City. I chose the month of May, when disasters such as the Moore Tornado of 2013 have occurred. This map uses a technique known as hexagonal binning, which employs a honeycomb grid to aggregate and visualize the data.

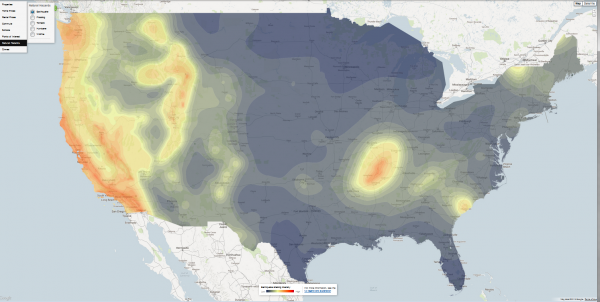

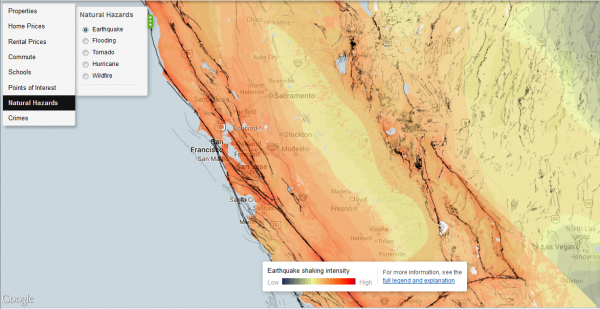

Earthquakes

Trulia’s earthquake hazard map shows potential shaking intensity and the system of faults. Here’s how Trulia summarizes the USGS data:

The data represent a model showing a 10% probability that ground motion will reach a specified level within 50 years. Shaking potential is calculated considering historic earthquakes, slip rates on major faults and deformation throughout the region, and the potential for amplification of seismic waves by near-surface geologic materials … Faults are represented as black lines on the map. Darker lines signify a larger slip rate, which is a measurement of how fast one side of the fault slides past the other side.

Everyone knows California and the West Coast is earthquake country, but I hadn’t realized how many other, inland areas are also susceptible to shaking. Below the national map is a close-up of central California.

Telling stories with Trulia

I was pleasantly surprised by the richness of data in Trulia’s maps. Its main competitor, Zillow, doesn’t have anything that comes close. Even if you’re not in the market for a house or thinking of selling, the website is a useful resource for learning more about your community.

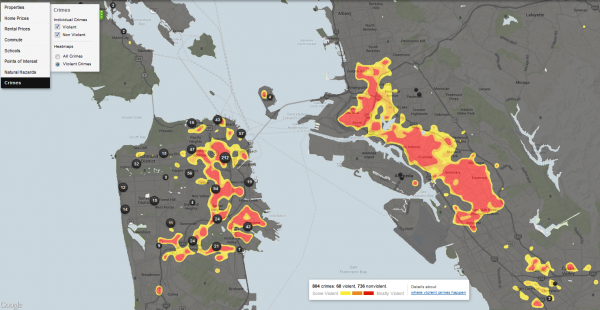

The geography of crime, shown below for the Bay Area, is a bit beyond our bailiwick here at EcoWest, but it’s certainly a key driver of growth and land-use patterns that have major environmental consequences (see this Trulia post for more on these crime maps).

Using Trulia, journalists, NGOs, researchers, and local policymakers can piece together a compelling portrait of a city or region by visualizing geographic patterns in crime, housing, transportation, education, and environmental hazards.

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.