The Colorado River, lifeblood of the Southwest, is in trouble. Demand for river water is rising as the region’s population continues to grow, but the Colorado’s inherently capricious supply is increasingly in doubt due to climate change.

A federal report released in December took an exhaustive look at the challenges facing the Colorado River Basin and it examined the options for dealing with expected shortages. I’ve gone through the Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study and pulled out the key figures, which you can download at the bottom of this post.

Colorado River Bain Study from EcoWest on Vimeo.

Shortage projected

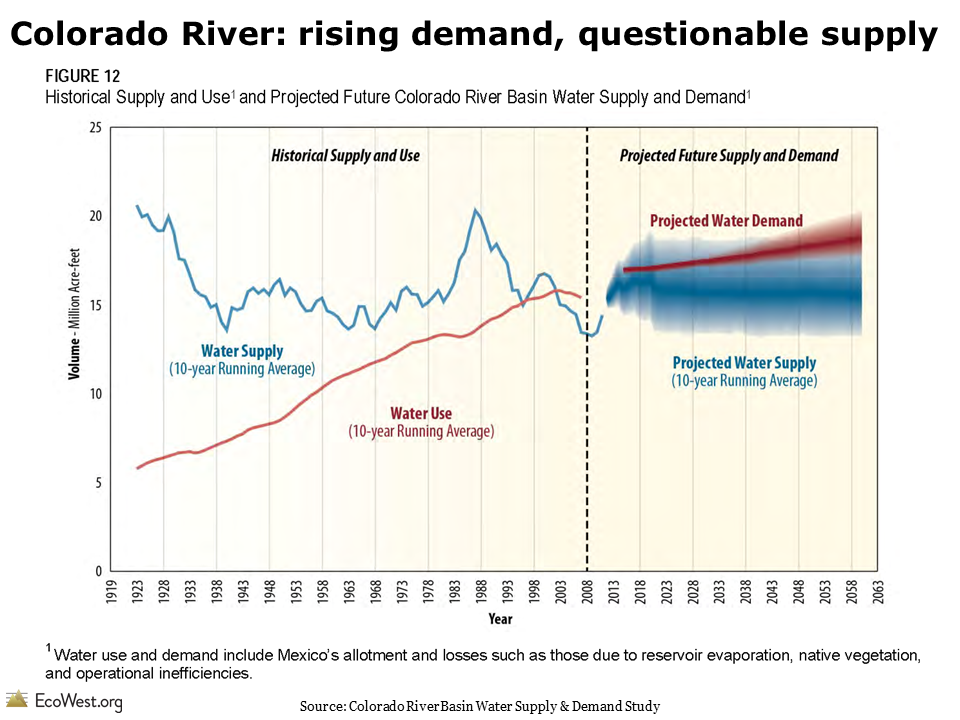

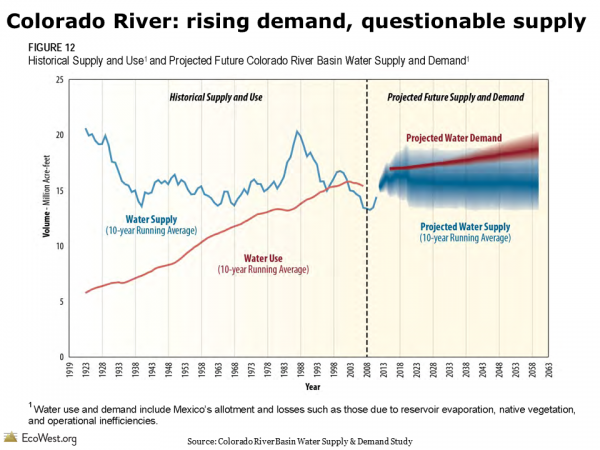

If I had to pick one graphic that summed up the dilemma facing the Colorado River, it would be this one:

Looking back in time, the graphic shows that water use in the basin steadily increased during the 20th century, but the river’s flow was predictably erratic (that blue line is a 10-year moving average but it’s still as uneven as the basin’s topography).

Looking ahead, water demand is expected to keep growing (the fuzzy areas indicate the uncertainty in the projections). Predicting the flow of the Colorado decades into the future is a tough task, but the study concluded that the supply would probably decrease, as indicated by the gentle downward slope of the blue line. By 2060, the imbalance between supply and demand is expected to be about 3.2 million acre-feet.

Comparing costs of solutions

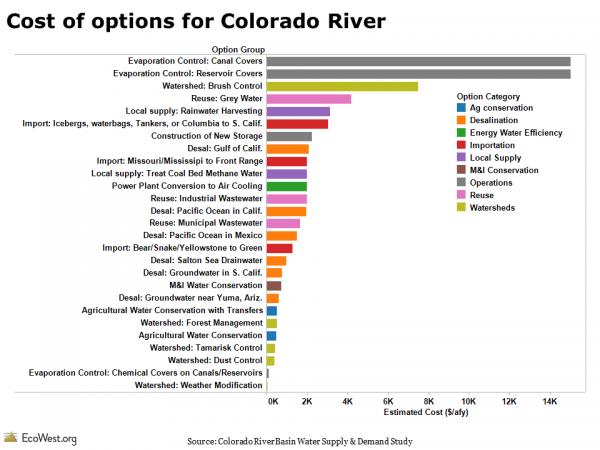

Besides identifying the problem, the Basin Study evaluated a wide variety of proposals for addressing the shortfall—everything from increasing water conservation in cities and on farms, to building massive new pipelines and desalination plants, even far-fetched ideas like towing icebergs to Southern California.

I extracted data from a summary table in the study in order to visualize how these options compare, both in price and in how much water they’ll yield.

In the graphic below, I’ve ranked all of the options from highest to lowest cost (the unit here is dollars per acre-foot per year). I’ve also color-coded them by category.

As you can see, the range of costs is enormous, but there are some general patterns. Conservation measures are among the cheapest, while desalinating ocean water or covering reservoirs to reduce evaporation are pricey. (For a few of these options, the study provided a range of costs, but for simplicity’s sake I’ve used the average in this graphic.)

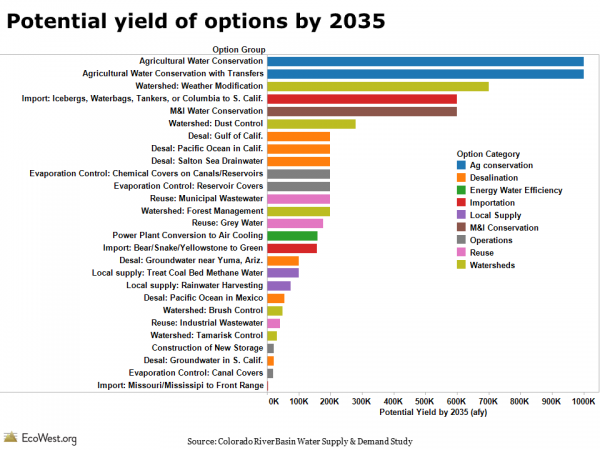

The chart below ranks the options by how much water they’re expected to yield in 2035.

Water conservation in agriculture and among municipal and industrial (M&I) users is projected to yield the most, but weather modification (aka cloud-seeding) also performs well on this measure.

I combined the cost and yield data into one graphic by varying the width of the bars by the volume of water that each strategy is expected to produce. The thicker the bar, the greater the yield. In this case, I used the projections for 2060, rather than 2035.

In releasing the Basin Study in December, federal officials stressed the conservation options over massive new infrastructure projects, such as pumping the Missouri or Mississippi rivers to the Colorado Front Range. These graphics show why that’s pretty much a no-brainer: conservation delivers more bang for the buck and avoids the enormous environmental impacts of augmentation projects.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Colorado River Basin Study (4115 downloads )

- Download Notes: Colorado River Basin Study (4854 downloads )

- Download Data: Colorado River Basin Study (4191 downloads )

Data sources

You can download the Basin Study and associated reports here.

The Denver Post had a good overview of the Basin Study’s release. See recent stories by the Los Angeles Times and Associated Press for more on what the federal government is doing to follow up on the report.

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.