When I was getting certified as a wildland firefighter in 2002, they taught us that fire behavior is based on three basic factors.

First, weather: not just the temperature, humidity, and wind at that moment, but also the climatic conditions over the preceding months and years. All else equal, if it’s hot, dry, windy, and you’re in a drought, you’d expect more extreme fire behavior.

Second, topography: drafty canyons, south-facing slopes exposed to the desiccating sun, and other natural features can encourage burning. Fire travels faster uphill, our instructors cautioned us, but firefighters move slower.

Third, fuels: the type of vegetation, its volume, its moisture content, and its continuity on the landscape. As a fire travels from grasslands to woodlands to dense forests, its personality can change radically.

The first two factors–weather and topography–are out of our control, putting aside the fact that we are changing the weather via climate change and loading the dice toward more fire-friendly conditions in the American West.

What we can directly influence are the fuels. We can break the natural cycle of wildfires by suppressing both human- and lighting-caused blazes, allowing the fuel to build up. We can mechanically thin and intentionally burn areas to reduce the amount of fuel available to future wildfires. We can go so far as to cut down all the trees and pave over a place, thereby eliminating the possibility of a wildfire (or a natural ecosystem).

Tracking fuels treatment to tame Western wildfires from EcoWest on Vimeo.

Fuels dilemma

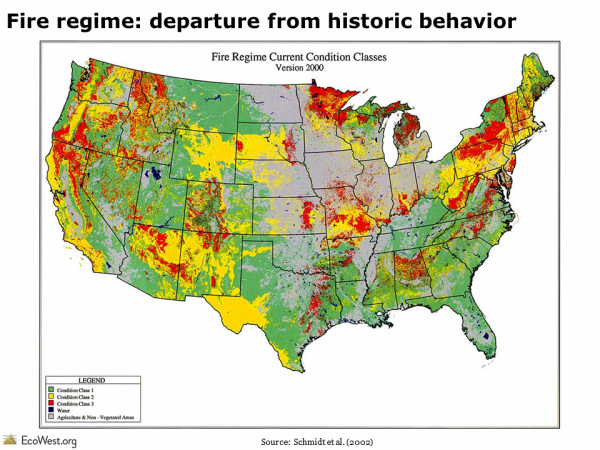

Today, the American West is facing a fuels dilemma. The graphic below shows the condition of fire regimes across the country. Red illustrates areas where wildfires may be significantly altered from their historic behavior, yellow shows areas that are moderately altered from historic conditions, and green marks where conditions are near historical norms. This data is from 2000, but things probably haven’t changed much since then.

I’ve created slides like these to describe the fuels dilemma in a PowerPoint you can download at the bottom of this post. The presentation explains how the policy of fire suppression has disrupted the natural fire regime in many parts of the West. I’ve also analyzed federal statistics on the number of acres thinned and burned, both in the slide deck and on this dashboard page, but the government’s reporting on fuels treatment is lacking and I’m still in search of better data to characterize this crucial issue.

Fuels treatment

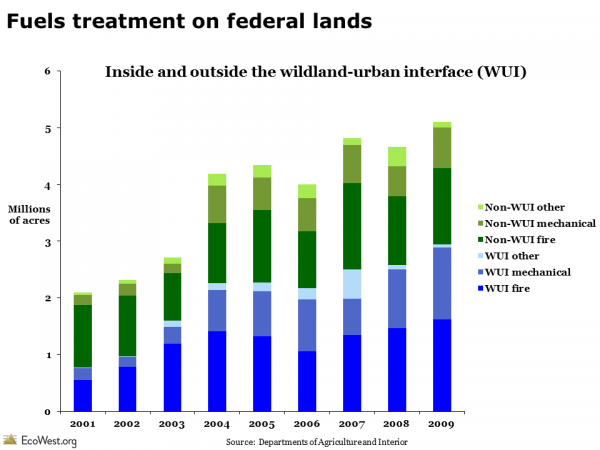

The graphic below distinguishes between a couple of different types of fuels treatment. The first distinction is between activity taking place within and beyond the wildland-urban interface. Known by its acronym, the WUI is where property and residents are at greatest risk of wildfires. The second distinction is between thinning with chainsaws (“mechanical”) and prescribed burns (“fire”).

The total acreage has been climbing in recent years, but the government only reports this data through 2009. I haven’t been able to find anything more current, but would welcome any suggestions from readers. The data source appears to have been created as part of the George W. Bush administration’s Healthy Forests Initiative but not continued by Barack Obama’s administration.

As of 2009, the federal government was treating an increasing number of acres, but it’s critical to remember that these totals are small relative to the size of the problem. Some 190 million acres of federal land face an elevated risk of catastrophic wildfire, according to one widely used estimate from the U.S. Forest Service (see here for technical report).

I was also struck by the considerable amount of thinning taking place outside of the WUI. Proposals to cut down brush and trees right around vulnerable communities often have the backing of environmental groups, but as these thinning projects move farther into the backcountry, they tend to face more opposition, especially if sizable timber harvesting is part of the equation.

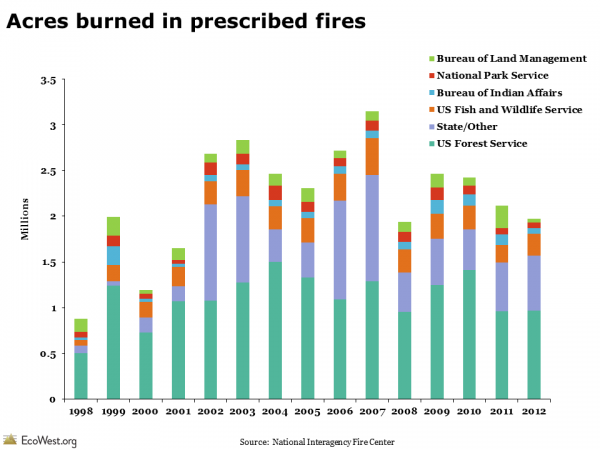

Prescribed burns

On a per acre basis, prescribed fires are much less expensive than mechanical thinning projects, but conditions have to be just right to set a prescribed fire so that it doesn’t turn into a disastrous wildfire. That’s happened occasionally in the West, such as the 2000 Cerro Grande Fire in New Mexico and the 2012 Lower North Fork Fire in Colorado that killed three people. Many in the public remain skeptical or outright opposed to prescribed burns because of the risks and smoke.

The graphic below shows that the number of acres burned in prescribed fires was increasing for a while, but the national total is just a couple million acres annually. (This time series, from the National Interagency Fire Center, is part of their annual report and looks like it will continue.)

Wildland-fire use

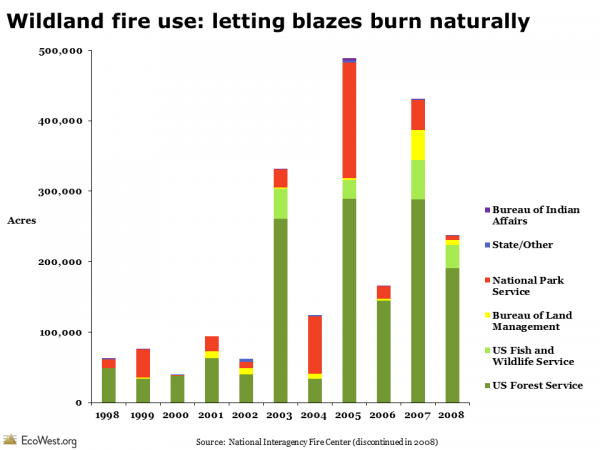

The federal government used to report on instances of “wildland fire use,” essentially letting wildfires burn rather than suppressing them. This strategy is still practiced today when fires are in a wilderness or other remote area and not posing a significant threat to property and people. The graphic below shows the number of acres burned in these types of fires, by agency, but the feds stopped reporting this statistic in 2008.

Looking ahead

In places like the Southwest, there’s pretty broad agreement among scientists, land managers, firefighters, and conservation groups that additional thinning in the WUI and increased prescribed burns could mitigate–but not eliminate–the risks of catastrophic fires destroying homes. The data I’ve found suggest there’s been a slight upward trend in such fuel treatments, but the overall totals are small and are likely to remain so in a time of fiscal austerity. Letting nature do the work for us would obviously be less expensive, even ecologically preferable, but the proliferation of homes in fire-prone landscapes has made fire suppression an imperative across much of the West.

Sources

Data on thinning comes from this report, part of a cooperative effort between the Interior and Agriculture departments. The information on prescribed burns and wildland fire use are from the National Interagency Fire Center.

This story from HowStuffWorks has a good discussion of the three key factors that explain fire behavior.

The Yarnell Fire disaster has generated some solid coverage of the wildfire issue. See this piece by Felicity Barringer of The New York Times on the rising number of homes in the WUI and this op-ed in the Arizona Republic by Don Falk of the University of Arizona. I’m quoted briefly in this story by Amanda Paulson in the Christian Science Monitor.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Wildfire Fuels (9751 downloads )

- Download Notes: Wildfire Fuels (9353 downloads )

- Download Data: Wildfire Fuels (10991 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.