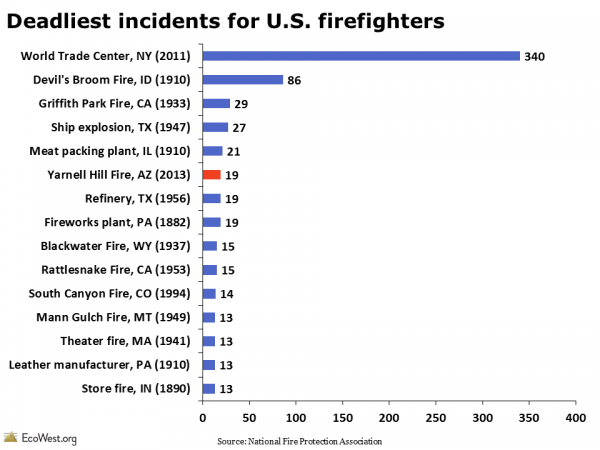

Wildfires were thrust into the national spotlight twice this year, first when 19 firefighters died in Arizona on June 30, and again in August, when the 257,314-acre Rim Fire burned in and around Yosemite National Park.

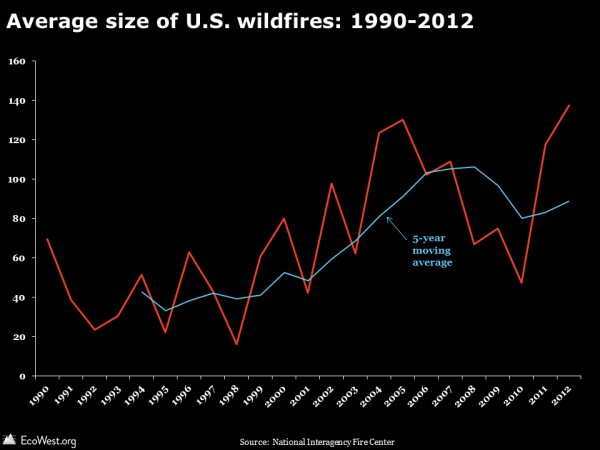

But if you look at the federal government’s statistics, 2013 is on track to be one of the quietest wildfire seasons in years. In the West and on Forest Service land, the season was closer to normal, but in the South and East, 2013 was a very quiet year for wildfires.

Year-to-date numbers

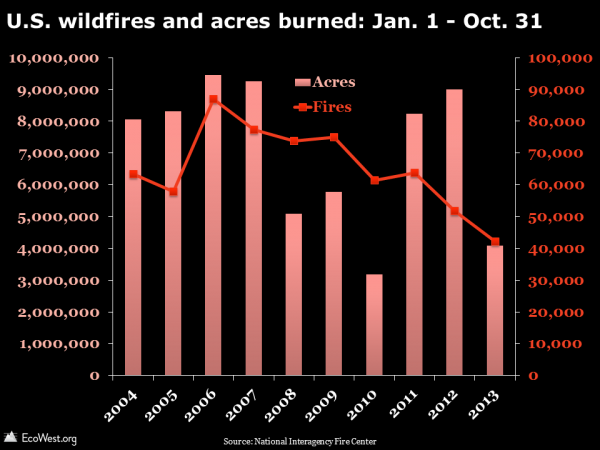

By the end of October, 40,775 fires had burned 4.1 million acres nationwide, which was only 63% of the 10-year average for the number fires, and just 59% of the 10-year average for acres burned (click on graphics to enlarge).

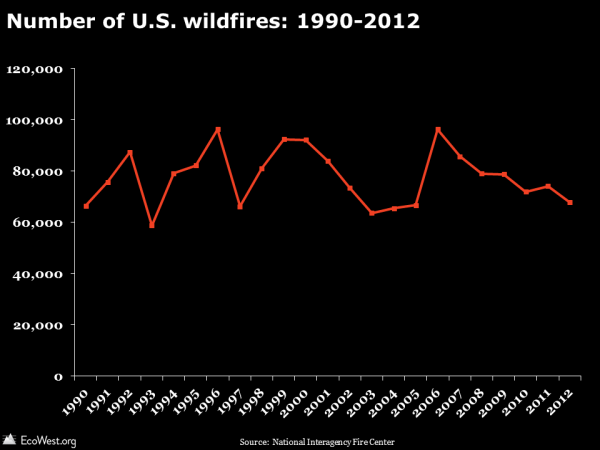

Some wildfires will break out between now and December 31, but the numbers aren’t going to jump as we head into winter. The time series below, for the full 12 months, shows that the lowest number of fires since 1990 was 58,810 in 1993, so unless there are more than 18,000 fires in November and December, 2013 is going to beat that record.

Regional breakdown

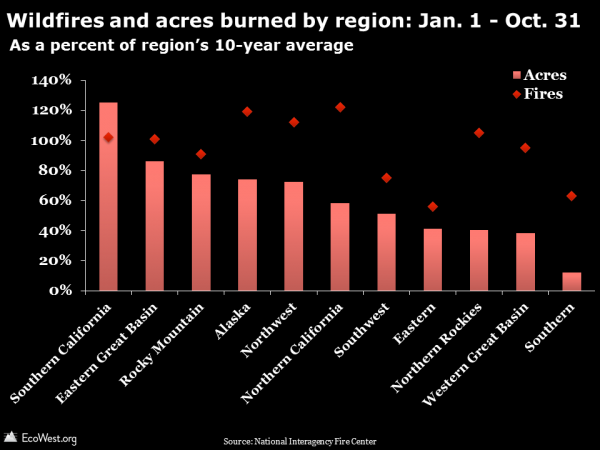

The graphics above illustrate national data. If you break it down by region, the number of acres burned has been below the 10-year average in every region except Southern California (which encompasses the Rim Fire).

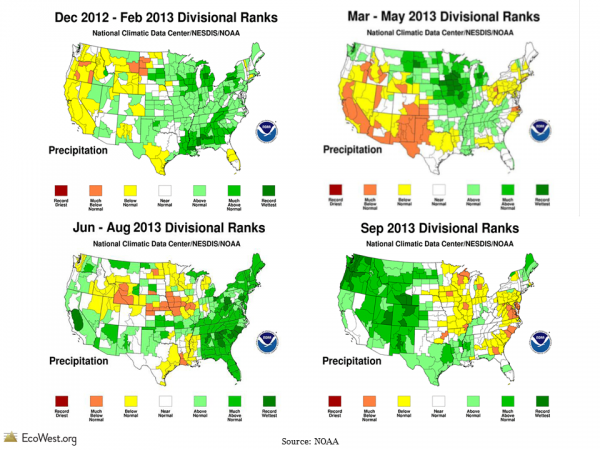

The chart below shows the Southern region is at just 63% of average for fires and 12% for acres, while the number of fires in the Eastern region is 56% of average and the number acres burned is 41% of average. Very wet conditions in the South and East in 2013 were responsible for the diminished fire activity and this played a big part in suppressing the national totals (a map of the regions is here).

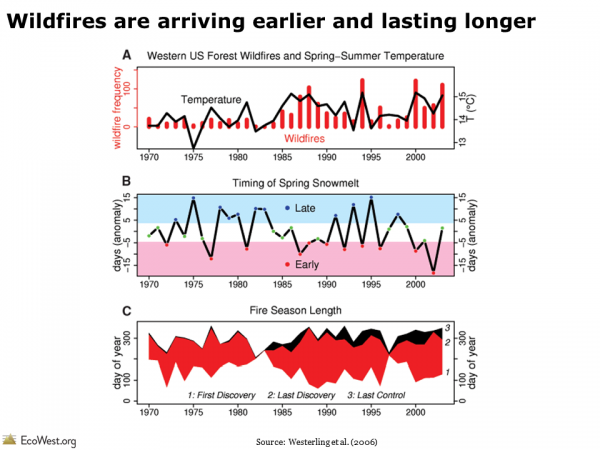

Going into the 2013 wildfire season, it looked like the West might be in store for a bad year. The preceding winter and spring were relatively dry, but some late spring storms and a strong summer monsoon in the Southwest reduced the danger. September was the wettest on record for many places in Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, as shown below.

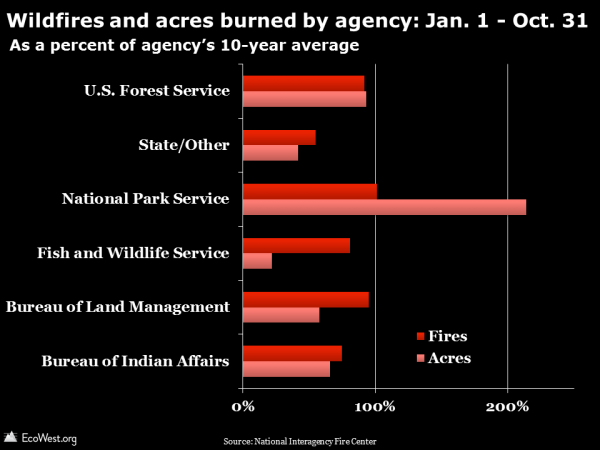

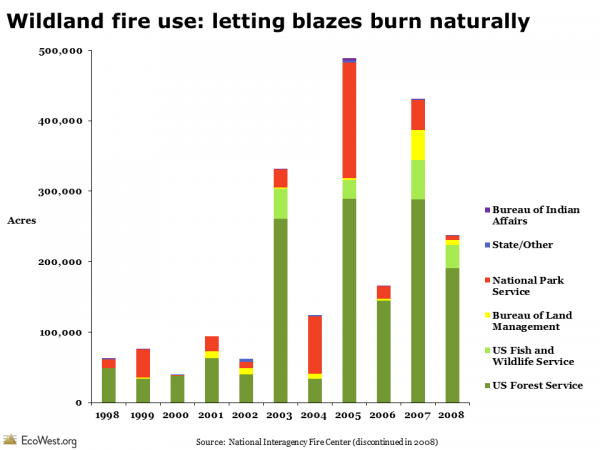

Fire activity by landowner

Another way to look at fire activity is by landowner. The National Park Service, which saw a chunk of Yosemite National Park burned by the massive Rim Fire, stands out in 2013. But other agencies had fewer fires and acres burned than average. On November 1, the Forest Service was at 92% of average for fires and 93% of average for acres burned. Much of the land in Southern and Eastern regions is private and you can see that reflected in the sub-average total for the “state/other” category, which includes private property.

Historic, below-average season

The 2013 season raised the profile of the wildfire issue like few other in recent memory, but if it weren’t for the Yarnell Hill disaster and the Rim Fire, I think we would have seen a fraction of the media coverage.

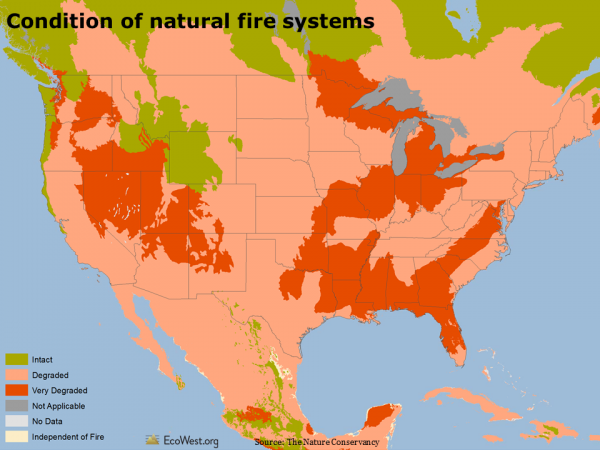

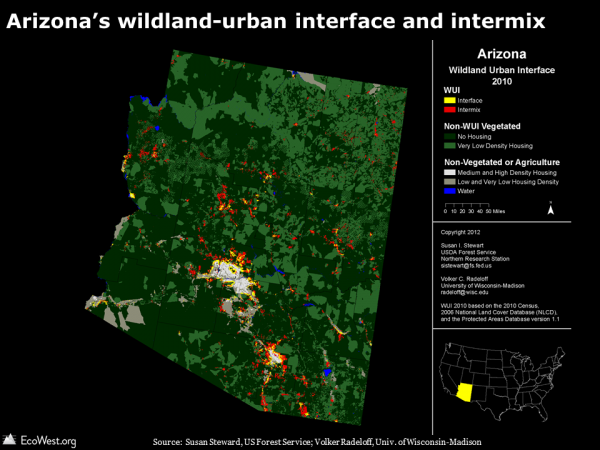

As I noted in a previous post, national-level wildfire statistics, while interesting and easy to grasp, can obscure more interesting stories happening at the local and regional level. Wildfire manifests in manifold ways in the United States. A lightning-sparked blaze in the Alaskan tundra can scorch a half-million acres of wilderness and claim not a single structure. An arson fire in the suburbs can burn a couple thousand acres and cause $1 billion in property damage.

What seems odd is that even in a slightly below-average year, the Forest Service has once again run out of money for wildfire suppression. Consider these excerpts from an October 30 E&E story with the headline “‘It’s just nuts’ as wildfires drain budget yet again.”

Lightning bolts rained across the West in August, sparking hundreds of wildfires in California, Oregon, Idaho and Montana and pushing the cash-strapped Forest Service to the brink. The service had at that point spent $967 million battling wildfires that had torched more than 3.4 million acres in 2013. Its emergency fund exhausted, it had about $50 million left — enough for about half a week … The Forest Service this year siphoned $505 million from budgets for research, capital improvement and reforestation accounts, among other programs, according to a memo obtained by Greenwire.

In a previous post, we showed that federal wildfire suppression costs are soaring, not only in the aggregate but also per acre and per fire. It’ll be interesting to see if the costs continue the upward march in 2013, even though this season has been relatively tame.

Data sources

The National Interagency Fire Center just published this summary of the 2013 wildfire season to date. NIFC provides data for the January 1 – October 31 time frame going back 10 years. It’s worth noting that if “average” were defined as the past 20 years or some other period, 2013 would rank differently.

Downloads

- Download Slides: 2013 Wildfire Season (6112 downloads )

- Download Notes: 2013 Wildfire Season (5736 downloads )

- Download Data: 2013 Wildfire Season (5408 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.