Like anglers who can dutifully pinpoint the location of hotspots, winter sports enthusiasts know when and where to find the best snow. When conditions change in the slightest—whether in temperature, base depth, or type of snow—devotees take note. But it can be hard to tell whether conditions on the local slopes in a given season reflect mere chance or long-term changes in global climate patterns.

In a previous post, we explored how rising greenhouse gas emissions will take an economic toll on snow-dependent sports. A 2012 report by two advocacy groups, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Protect Our Winters, provided an indicator of how climate change may impact snow sports. The study estimated that the $12.2 billion winter sports industry has already felt the pinch of decreased snowpack and escalating average winter temperatures; under a business-as-usual trajectory, future scenarios appear even bleaker (see our dashboard of their data).

In this post, we dive deeper into what the science is telling us about climate-driven trends in the Western snowpack.

Observed trends in mountain snowpack

In the coming decades, changes to the West’s snowpack will create ripple effects far beyond the ski slopes. Near-term changes in the region’s hydrological cycle will impact water supplies, forest health, agricultural productivity, and the food supply. The bulk of the flow in most Western rivers comes from melting snow.

Describing changes in snow hydrology, one climate scientist framed it succinctly: “Shorter snow season, less snow overall, but the occasional knockout punch. That’s the new world we live in,” said Michael Oppenheimer of Princeton University.

To measure how the snowpack has been changing, scientists often gauge snow levels on April 1st, which is when the snowpack usually reaches its basin-wide maximum in the West. The amount of April 1st snow water equivalent (SWE) has shown a downward trend in recent decades: across the Cascades of the Pacific Northwest and in much of California, the SWE level has decreased 20% compared with 80 years ago.

Scientists have shown that most of the large-scale reductions in snowpack have been related to rising temperatures. Temperatures have warmed by 2 degrees Fahrenheit in the Rocky Mountains and by 1.7 degrees in the Sierras.

According to Anne Nolin, professor of geosciences and hydroclimatology at Oregon State University, the spring snowpack has been declining by 1.5-2% per decade over the past several decades. While this amount may not sound like a steep change, it is significant enough to cause economic losses for the ski areas most vulnerable to a changing climate, such as those at lower elevations and in the warm extents of the Pacific Northwest.

Though overall projections anticipate a consistent decline in Western snowpack over the 21st century, these are difficult predictions to make given the great variability in snowfall from place to place and year to year. As winter sports fans are well aware, resorts separated by only a few miles can receive vastly different snow totals from a single storm.

Another challenge scientists face is the lack of long-term datasets. One key source is SNOTEL, which is operated by the Natural Resource Conservation Service and tracks variables such as precipitation, temperature, snow depth, and soil moisture at more than 600 sites in 13 states. However, the installation of SNOTEL began in the mid-1970s, and thirty years can be a narrow window for distinguishing between climatic changes and natural variability. For this reason, many climate scientists rely on temperature data, which tends to be less variable than precipitation data and which can reveal broader patterns based on 30-50 years of measurement.

Future trends: more rain, less snow, and earlier snowmelt

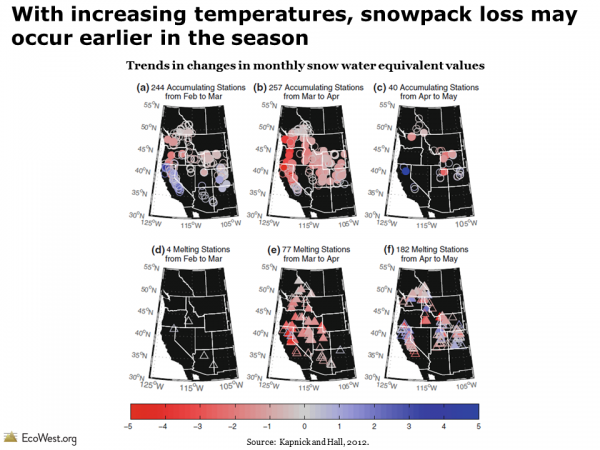

Under a business-as-usual scenario, winter temperatures are projected to warm by an additional 4-10 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of this century, which could lead to a 25-100% decline in snow depths in the West.

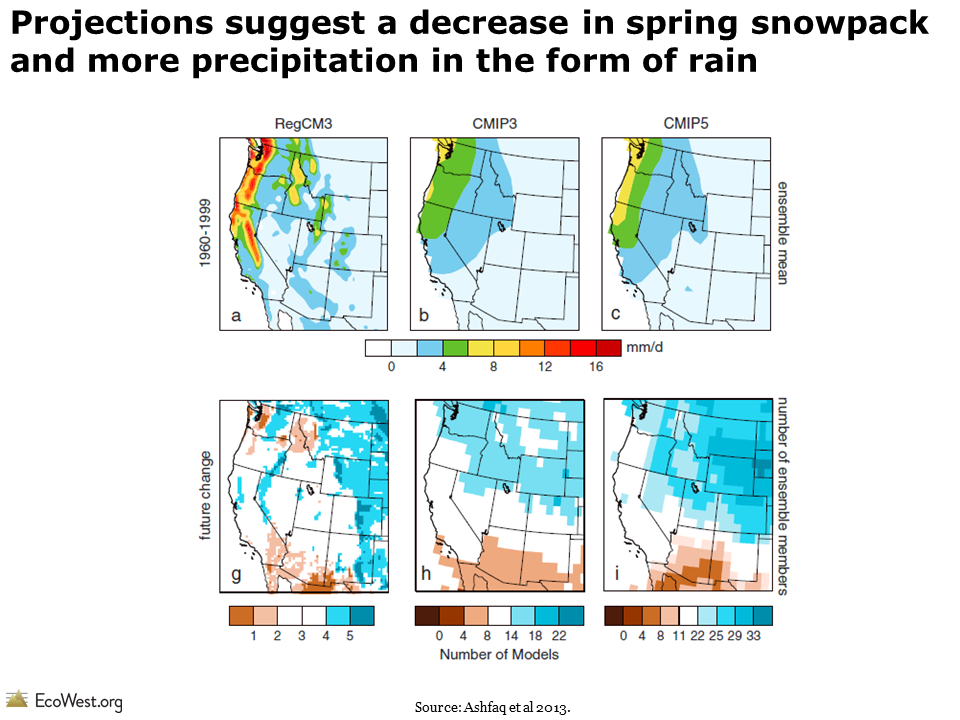

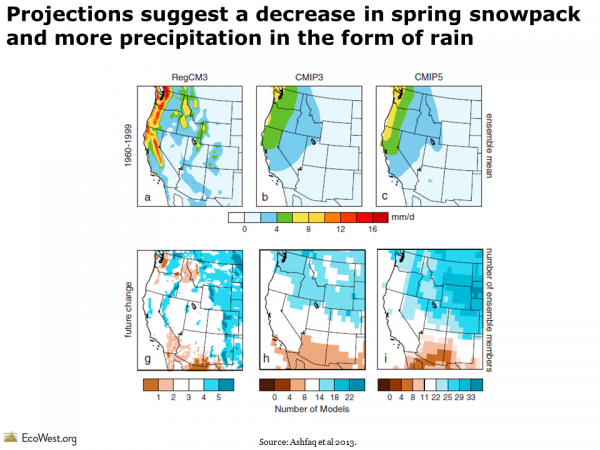

Although there is still considerable uncertainty, models predict a decrease in spring snowpack, a transition from snow to more rain, and a reduction in summertime streamflows across the West. By 2040, increased temperatures could melt most of the snowpack in the Sierras and Colorado Rockies by April 1st.

Mountainside winners and losers of climate change

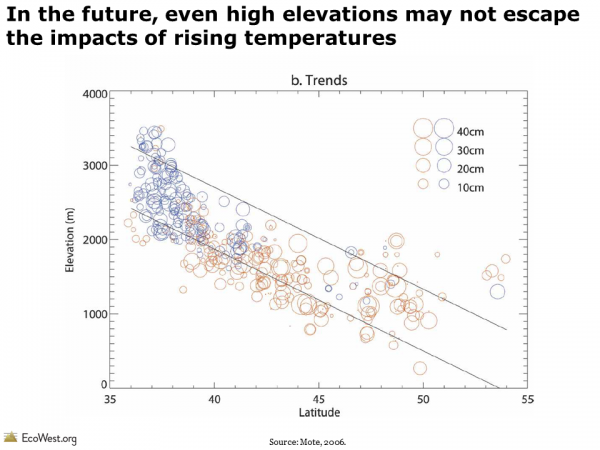

The impacts of a changing climate will play out differently across the West. Lower elevation areas, such as the Pacific Northwest, are more sensitive to warming temperatures and may be the first locations to feel the impact of snow turning to rain. On the other hand, Colorado has some built-in resilience since it has more ski slopes above 9,000 feet than any other Western state. But over the long term, even high-elevation locations may not be immune to the impacts of a changing climate.

In the near term, the first victims of climate change in the winter sports industry are likely to be the roughly 300 small mom-and-pop ski resorts. Many of these operations are situated at lower elevations and operate on slim financial margins. While megaresorts can compensate for low-snow years with extensive snowmaking infrastructure, smaller mountains may find such systems beyond their financial reach.

If mom-and-pop ski areas go under, it could have a big impact on the future of the American ski industry. These smaller resorts are sometimes referred to as “feeder breeders” because they provide an entry point for people learning to ski and snowboard before they graduate to steeper slopes on bigger mountains or in the backcountry.

While winners and losers may emerge in the near term, ultimately the entire winter sports industry could suffer if the shrinking snowpack turns skiing and snowboarding into fringe activities. “Colorado may have a strategic advantage,” said Nolan Doesken, state climatologist for Colorado, “but if there’s not a national or international interest in winter sports, it could ultimately disadvantage even Colorado. When the entire country struggles with snow and the demand for skiing is lower, the whole industry is at risk.”

Climate contradiction: more blizzards, but less snow overall

During the climate bill discussions in the Senate in 2010, climate change skeptic Senator James Inhofe (R-OK) constructed an igloo on the Capitol Lawn during the record Mid-Atlantic snowstorm, coined “snowpocalypse.” While Inhofe meant to suggest that climate change is hoax, scientists in fact have been warning for some time that a world with warming temperatures is poised to trigger more potent blizzards.

Since a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, it is reasonable to expect an upward trend in extreme winter precipitation, in the form of both rain and snow. During the past 50 years, the United States has seen twice as many extreme snowstorms as experienced during the previous 60 years.

“Strong snowstorms thrive on the ragged edge of temperature—warm enough for the air to hold lots of moisture, meaning lots of precipitation, but just cold enough for it to fall as snow,” said Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center. “Increasingly, it seems that we’re on that ragged edge.”

Data sources

- Ashfaq et al, 2013. “Near-term acceleration of hydroclimatic change in the western U.S.” American Geophysical Union, 118, 10,676-10,693.

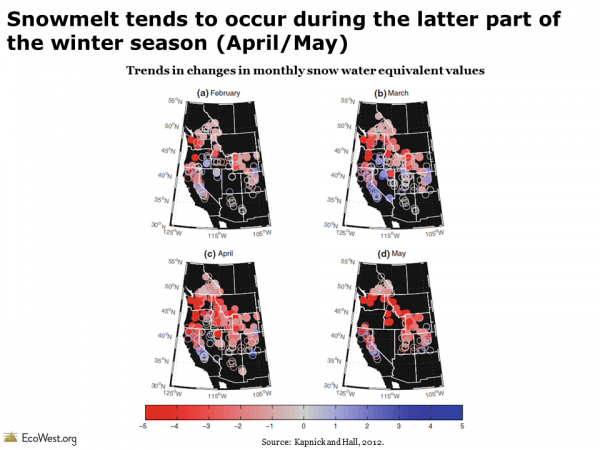

- Kapnick, S. and Hall, 2012. “Causes of recent changes in western North American snowpack.” Climate Dynamics, 38, 1885-1899.

- Mote, P., 2006. “Climate Driven Variability and Trends in Mountain Snowpack in Western North America.” American Meteorological Society, 19, 6209-6220.

- Pierce et al, 2008. “Attribution of Decline Western U.S. Snowpack to Human Effects.” American Meteorological Society, 21, 6425-6444.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Climate Change and Western Snowpack (7091 downloads )

- Download Notes: Climate Change and Western Snowpack (8043 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.