The preponderance of public land is one of the American West’s defining features and it’s a primary reason why so much of the region has escaped the kind of intensive development that characterizes most areas back East.

In this set of slides, I examine the lay of the land in the West and explain how the mosaic of ownership has shaped the region’s evolution. Although the federal government is the biggest player in the region, the future of the West’s environment also hinges on state, tribal, and private land-management decisions.

Land ownership in the American West from EcoWest on Vimeo.

Federal government biggest land owner

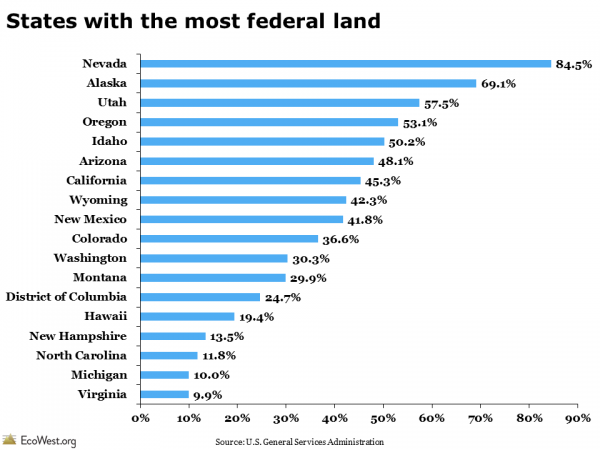

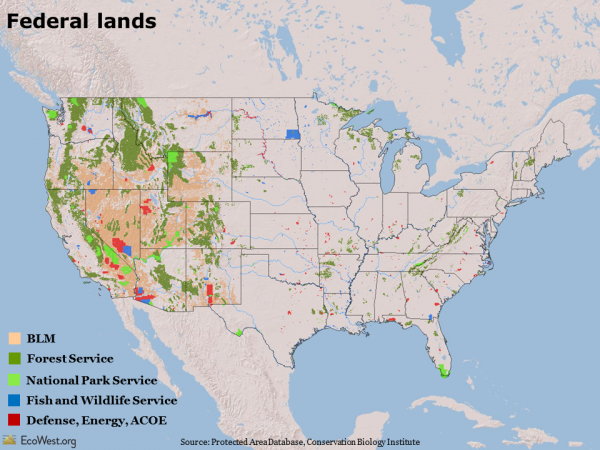

The U.S. government owns nearly half of the 11 Western states, but those federal acres are managed very differently by a host of agencies with varying mandates. Wilderness areas within national parks or wildlife refuges ban nearly all human development, while some Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management properties are more like industrial zones, with priority given to intensive logging, mining, drilling, grazing, and motorized recreation. The graphic below, based on a similar map in a 2008 Stanford magazine article, shows what share of each state is federal land.

In some parts of the West, such as the Great Basin in Nevada, it seems like the federal government owns everything in sight. But these slides show that the level of federal influence varies dramatically across the region. At the low end, about 30 percent of Montana and Washington land is federally owned; at the top, Nevada is nearly 85 percent federal. There’s also considerable variability within individual states: the plains of eastern Colorado, for example, are nearly all private, while the Rocky Mountains in the center of the state are predominantly federal.

In an incredibly diverse region, it’s hard to envision a “typical” Western landscape, but there’s a general pattern in ownership. Pioneers tended to settle around streams and rivers, so many of the West’s vital watercourses are surrounded by private land (such lands often harbor the greatest biodiversity). Mountain ranges are often under the purview of the Forest Service, with wilderness areas sometimes found at the highest elevations (where biodiversity and biological productivity tends to be lowest). In the basins between these ranges, the Bureau of Land Management tends to dominate the drier, lower-elevation areas.

Tribal and state land also critical

There are other key players. Tribal land, which covers large portions of Arizona and New Mexico, is found in every Western state. Military training and weapons experiments take place on lands controlled by the departments of Defense and Energy. Some of these places, such as the fabled Area 51 in Southern Nevada, are top secret, but portions of others, such as the Barry M. Goldwater bombing range in Southwest Arizona, are open to recreational users who get a special permit.

Especially in the West, but also in some parts of the upper Midwest and Northeast, state governments control a fair amount of land. Out West, these acres were generally given to the states by the federal government when territories entered the union. Typically, states are supposed to raise money for their public schools by selling some of these lands to the highest bidder, so protections for these areas are far from permanent.

Because there’s so much public property in the West, many landscapes are at least nominally protected by the government. But public ownership doesn’t equal immunity from human influence. As I discuss in another post, the vast network of roads and other infrastructure in the region has fragmented habitat and abetted the spread of non-native species. The multiple-use philosophy that governs much of the property overseen by the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management means natural resources may be vulnerable to development and human activity.

What patterns in land ownership do you notice in these slides?

Downloads

- Download slides: land ownership in the West (5789 downloads )

- Download notes: land ownership in the West (6849 downloads )

- Download data: land ownership in the West (6021 downloads )

Data sources

The maps of land ownership come from the Protected Area Database. This data from the Conservation Biology Institute is available for free download on DataBasin.

Other valuable sources of data on land ownership include the Bureau of Land Management’s Public Land Statistics report, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, and the U.S. General Services Administration’s Federal Real Property Profile (the latest report is from 2004, but these figures haven’t changed much in recent years).

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.