For the past few years, Colorado College’s State of the Rockies Project has been conducting a Conservation in the West poll, and the results continually show strong support for protecting the West’s environment.

When voters in six states are asked about issues such as energy development, safety regulations, and public lands, they tend to prefer renewable technologies, keeping a close watch on business, and protecting open space for habitat and recreation. But there are some interesting regional differences, especially when it comes to energy.

We’ve created a short PowerPoint presentation, available for download at the bottom of this post, that summarizes some findings from the Conservation in the West polls. You can also view the slide deck in this embed:

Annual poll of Western voters shows strong support for conservation from EcoWest on Vimeo.

Limited sources on Western environmental public opinion

In an earlier post, we discussed the national-level results from Gallup’s polling on the environment. In some cases, Gallup has been asking the same question over and over, year after for year, for decades.

Unfortunately, we haven’t found any comparable public opinion surveys of the West that offer such a lengthy time series. Some states in the region have longstanding surveys, such as California’s Field Poll, which was established in 1947. The Public Policy Institute of California also puts out a yearly poll on the environment.

But when it comes to understanding how Westerners think about things like wildlife, carbon regulations, and the water supply, the best source we’ve found is Colorado College’s yearly polls. Here’s how The New York Times summed up the 2013 results:

Nine in ten people polled said that national parks, forests, monuments and wildlife preserves are essential to the economy. Three in four said that those lands furnish good jobs, and more than seven in 10 said that no public lands should be sold to private corporations. Three in five said that drilling should not be allowed in “critical locations” near recreation areas, water sources or wildlife. Only 35 percent said that more public lands should be opened to “responsible energy development.

In tandem with two pollsters (Lori Weigel of Public Opinion Strategies and Dave Metz of Fairbank, Maslin, Maullin, Metz & Associates), Colorado College conducted a survey of 2,400 voters in six Western states: Arizona, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

Environment vs. economy: false dichotomy?

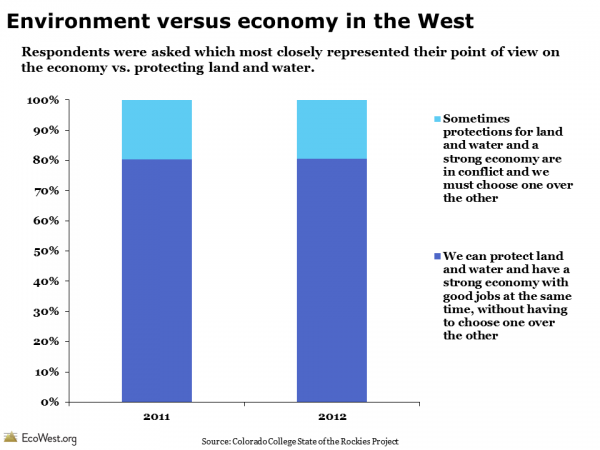

Although we hear a lot about the environment versus the economy, nearly 80 percent of respondents said we can simultaneously protect land and water while maintaining a strong economy.

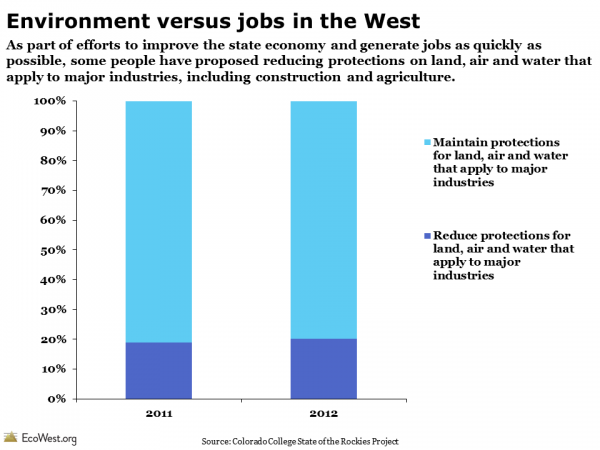

Below are the results from a similar question, which asked respondents whether they favored “reducing protections on land, air, and water” that apply to businesses in order to help the economy and generate jobs as quickly as possible. Fewer than one-fifth of Westerners supported that proposition.

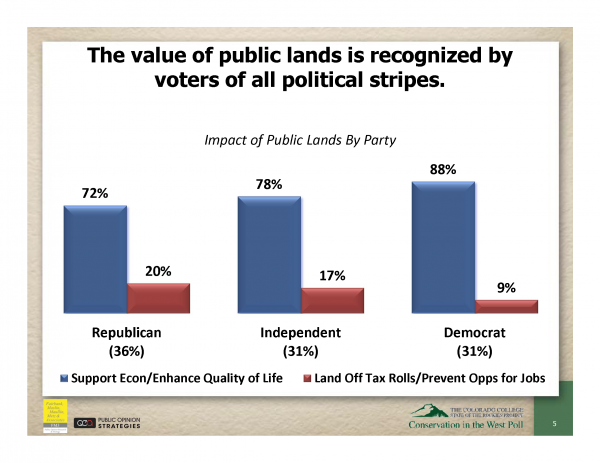

Strong support for public lands

Regardless of political affiliation, the vast majority of Westerners believe that public lands support the economy and enhance the region’s quality of life, rather than “take land off the tax rolls, cost government to maintain them, and prevent opportunities for logging and oil and gas production that could provide jobs,” as shown in graphic below.

Diversity in state opinion on energy

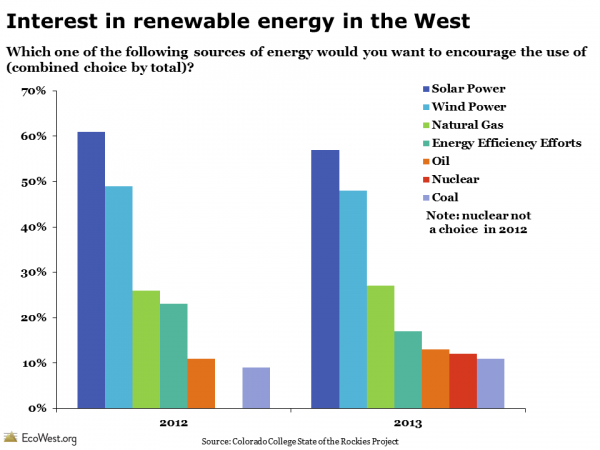

Many of the questions in the past three years of polling have related to energy. When asked which energy sources they’d like to encourage, solar and wind power come out on top and coal is at the bottom. Of the fossil fuels, Westerners favor natural gas, even rating it above energy efficiency efforts. The results are similar when people are asked about what energy sources they’d like to discourage.

Regional views on energy

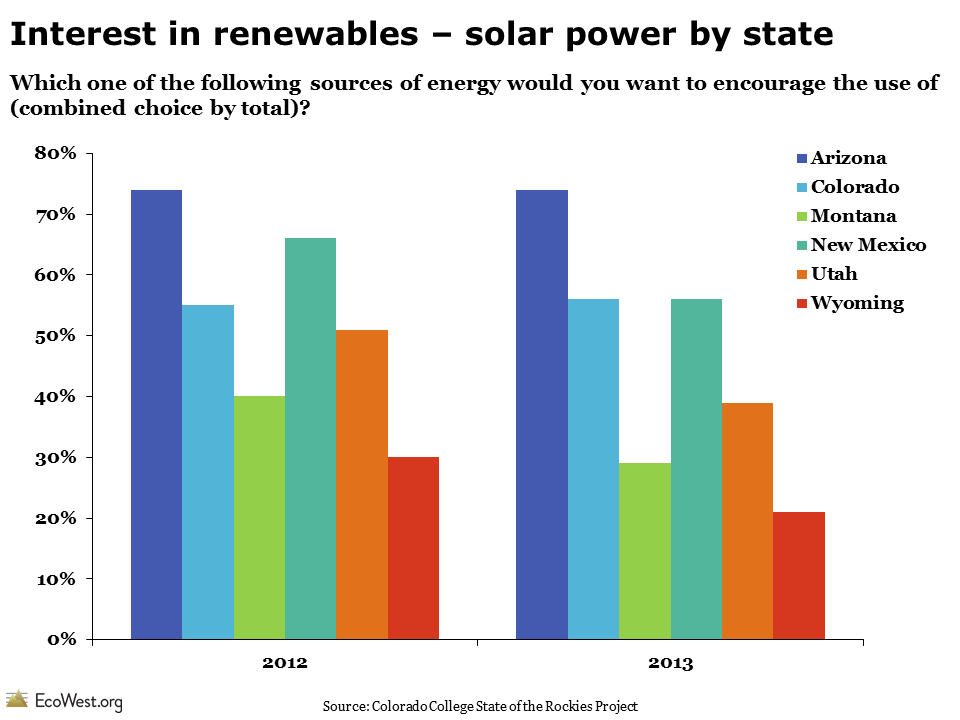

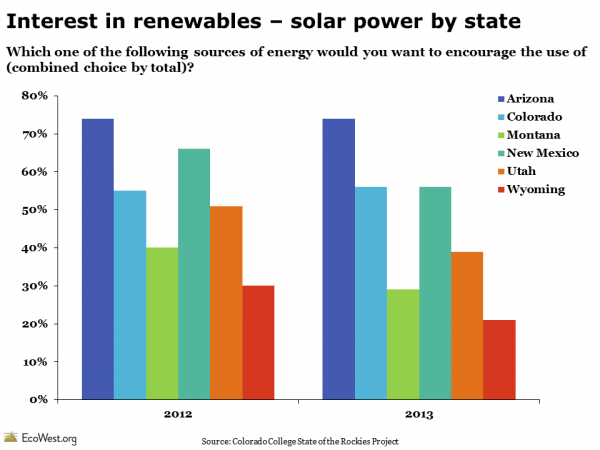

As we discuss in a previous post, the nation’s energy resources, both fossil and renewable, are not evenly distributed, so it’s no surprise that there are some significant differences among state residents when it comes to their energy preferences. The graphic below shows that in Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico, majorities want to encourage solar, but support is lower in the other states and fell between 2012 and 2013 in Montana, Utah, and Wyoming

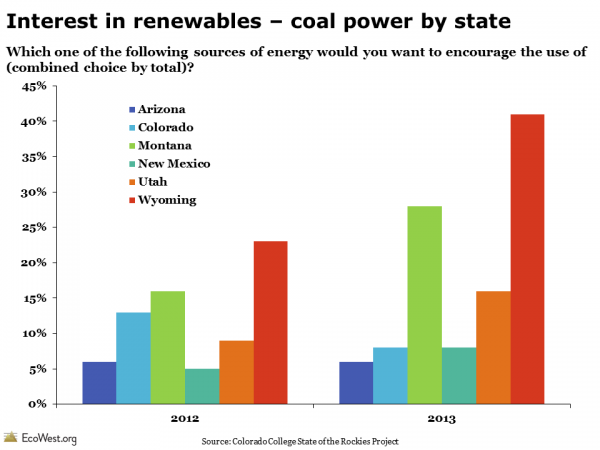

When asked about encouraging coal as an energy source, Wyoming stands out. No surprise there: it’s the largest coal-producing state in the country. There was also a large jump in support for coal from 2012 to 2013 in Wyoming, Montana, and Utah, but a decrease in support in Colorado. Perhaps the growing support for coal in some states is a backlash against increasing federal regulation of the fuel source.

Hopefully, the State of the Rockies project will continue to commission this poll so that we can keep tracking changes in Western public opinion in the years to come. If you find other surveys on Western environmental issues, please let us know.

Data sources

You can download data from the 2013 poll, a presentation summarizing the results, and state-level reports on this page. Results from 2011 and 2012 are also available.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Conservation in the West Survey (5610 downloads )

- Download Notes: Conservation in the West Survey (6010 downloads )

- Download Data: Conservation in the West Survey (5324 downloads )

Thanks to Micah Day for assistance with this post.

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.