The Western wildfire season is well underway, so I thought this would be a good time to examine a key question: what causes wildfires?

Basically it boils down to two ignition sources—humans and lightning—but the balance between these two causes varies dramatically across the country. We have a dashboard on ignition that illustrates the data and I’ve created a PowerPoint presentation that you can download at the bottom of the post.

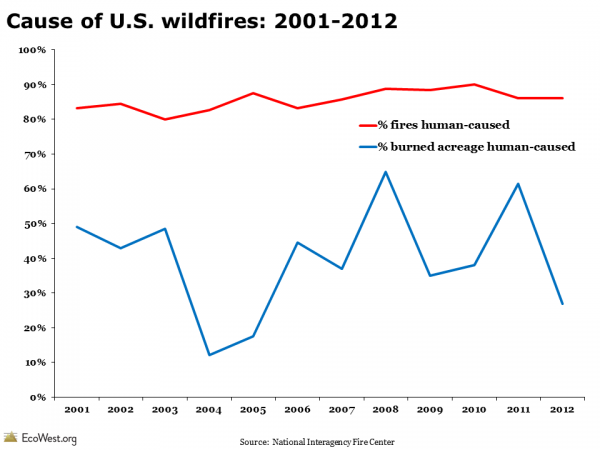

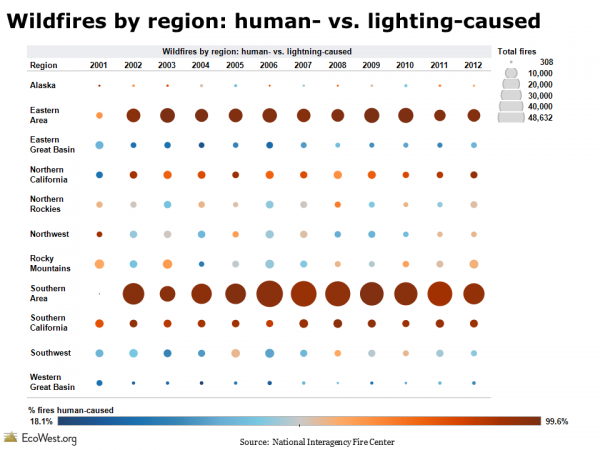

This graphic summarizes the national picture since 2001:

Two metrics: fires and acres

Over the past dozen years, more than 80 percent of all wildfires have been caused by people and that rate has been very steady. But if you look at the acreage burned, as opposed to the number of fires, humans are usually responsible for less than half the total.

Why the difference? Lightning-sparked fires in remote parts of the West and Alaska may get very large before they are contained; in some cases, these blazes are allowed to burn to reduce fuels. By contrast, many human-caused fires start in populated areas and are quickly controlled.

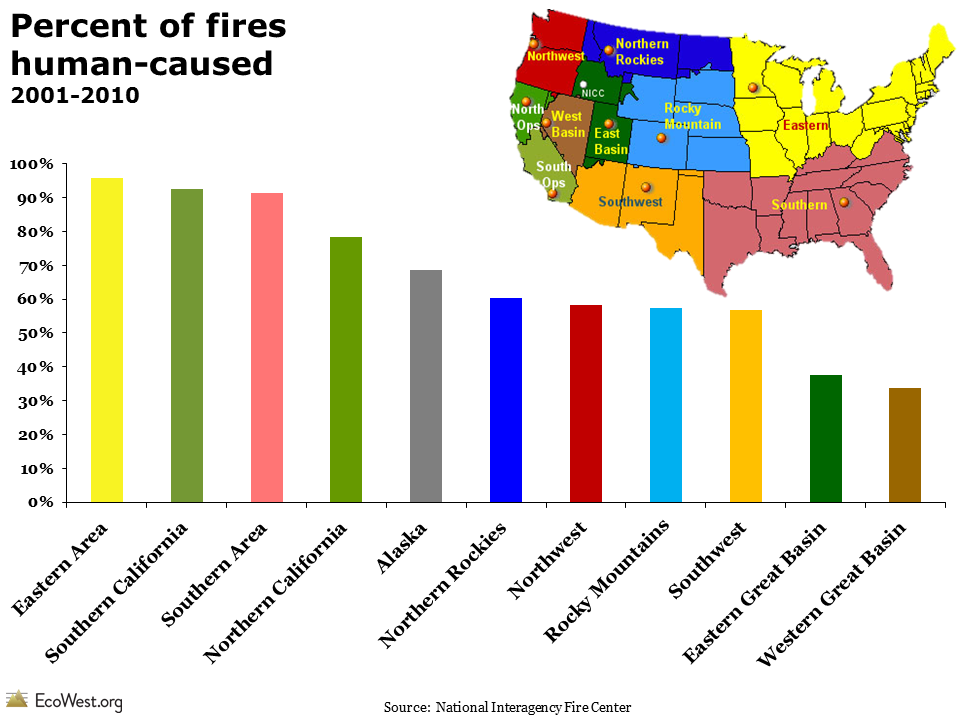

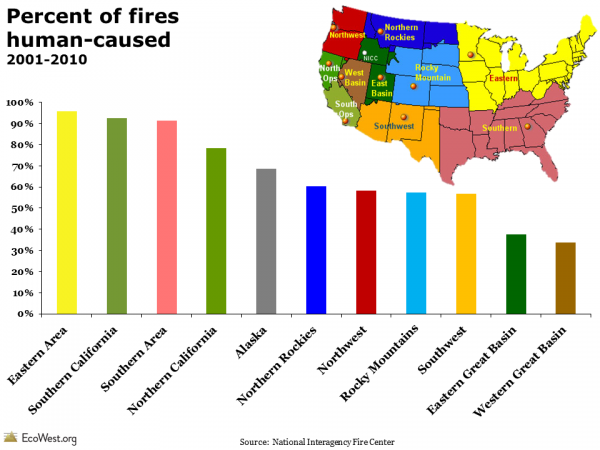

You can see the regional differences in the chart below, which shows what percent of fires were human-caused from 2001 to 2010. The regions are defined by the National Interagency Fire Center.

Back East and in California, humans are responsible for starting the vast majority of fires, whereas in the Great Basin, it’s less than 40 percent. This regional breakdown suggests that fire prevention programs will be more effective in some areas than others.

Explore data in our dashboard

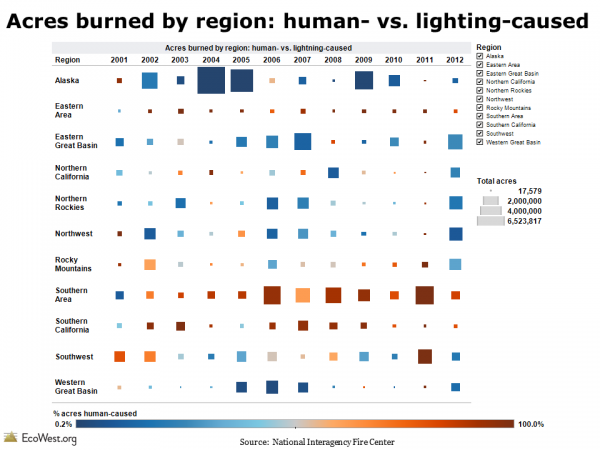

Our wildfire ignition dashboard presents this information in a different way and allows you to interact with the data. The screenshot below shows the number of acres burned in each region:

There have been some huge wildfires up in Alaska and nearly all the acreage burned was due to lightning-sparked blazes. Conversely, human-caused wildfires predominate in the Southern area. In other regions, such as the Southwest, the situation is more variable. In some years, humans are responsible for the bulk of acres burned, but in other years most of the burning is due to lightning

The screenshot below shows the number of wildfires in each region. The Southern and Eastern regions, where the bulk of the nation’s population lives, have the greatest number of human-caused wildfires, but in places like the Great Basin, where relatively few people live, the vast majority of fires are caused by lightning.

Takeaways

The large number of lightning-caused fires out West should remind us that wildfires are inevitable in the region. Measures like campfire bans and public lands closures, which may succeed in cutting the number of human-caused fires, can only do so much.

This data also illustrates why it’s so important for us to get beyond national-level statistics when analyzing wildfires. Otherwise we end up lumping together lightning-caused blazes in the unpopulated Alaskan tundra and arson fires in the chaparral of suburban Los Angeles.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Wildfire Ignition (5223 downloads )

- Download Notes: Wildfire Ignition (5743 downloads )

- Download Data: Wildfire Ignition (5328 downloads )

Data sources

The National Interagency Fire Center publishes data on the cause of wildfires on this page.

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.