[6/30/2013 UPDATE: see this post for more details on how the deaths of 19 firefighters in the Yarnell Hill Fire rank historically]

I’m sorry to say that some wildland firefighters are likely to die in the coming months. Over the past decade, an average of 18 people have been killed each year while trying to suppress U.S. wildfires.

I’ve created a dashboard to track fatalities among U.S. wildland firefighters and put together a short presentation that you can download at the bottom of this post along with the data.

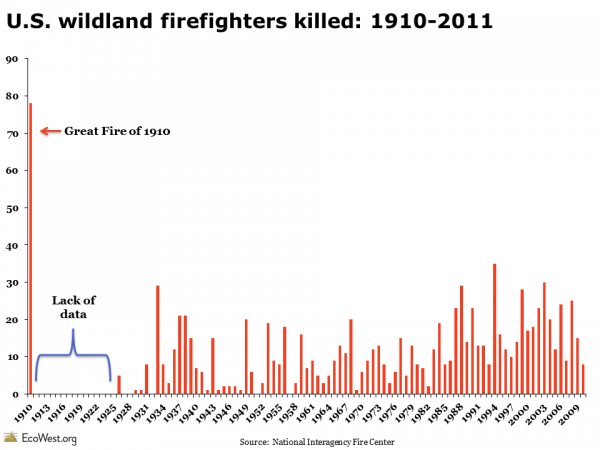

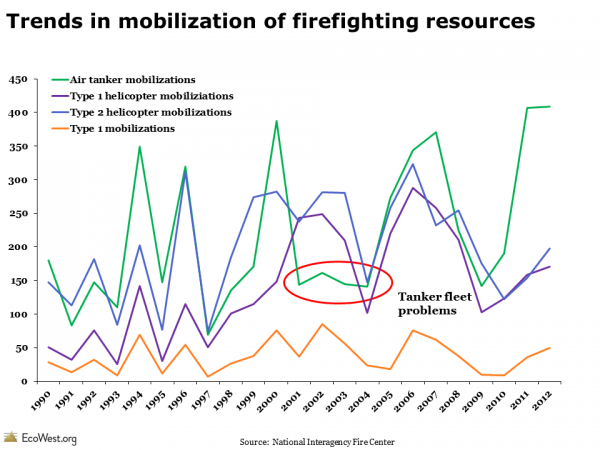

As we discuss in our fire slide deck, the Western wildfire season is getting longer and fires are burning more intensely in many places, so I was curious whether there had been an uptick in the number of firefighter fatalities. There is, in fact, a slight upward trend in deaths, but that may be due to an increasing number of firefighters deployed, rather than the job becoming riskier.

More than 1,000 killed

Wildland firefighting remains a dangerous business, with at least 1,030 people killed in the line of duty since the Great Fire of 1910 in the Northern Rockies. The government reports no deaths for the subsequent 15 years, which I’m assuming is due to a lack of data, and the most recent data available is from 2011.

Cause of death

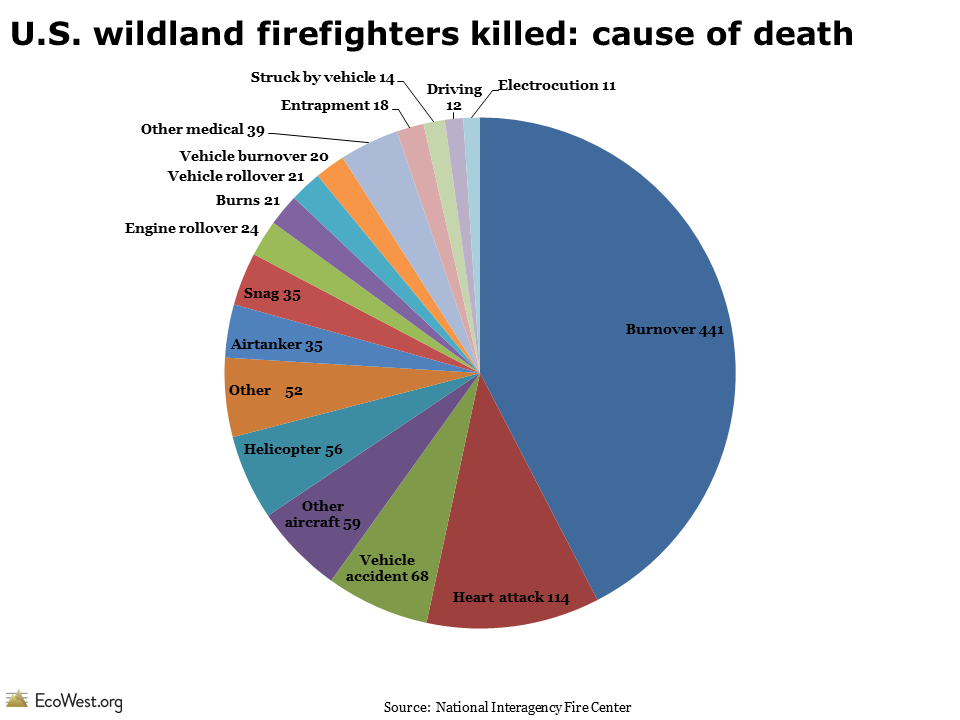

The most common way that wildland firefighters die is when they are overrun by flames. Such burnovers account for 42% of all deaths in the database, as shown in the pie chart below.

The next leading cause is heart attack. Fighting fires by hand is grueling physical work and it’s not unusual to see wildland firefighters in their 40s or 50s. When not fighting fires, many work for land management agencies, such as the Forest Service, Park Service, and Bureau of Land Management.

The other trend that jumps out of this morbid data is the perils of driving and flying around wildfires. There were 288 fatalities related to airplanes, helicopters, and vehicles, or about 28% of the total.

Most deaths in West

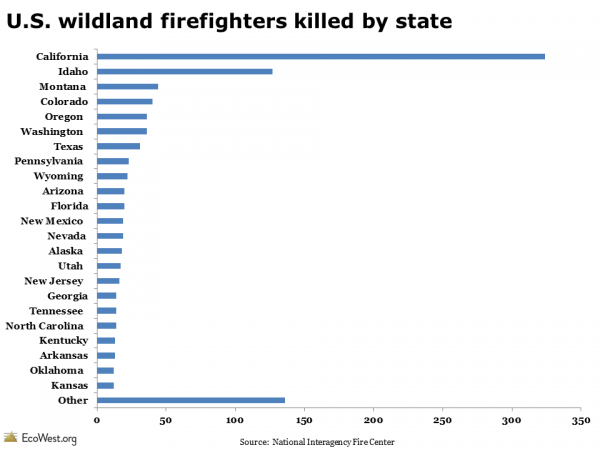

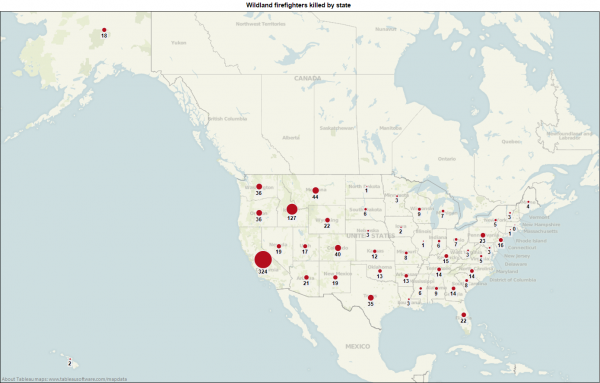

Wildland firefighters have died in every state except Massachusetts. Eight of the top 10 states for wildland firefighter fatalities are in the West, with California leading the way by far.

The map below, from our dashboard, shows the geographic distribution of fatalities.

Inherently dangerous work

I’ve been fascinated with wildland firefighting ever since I was certified, or “red-carded,” in 2002 by the Coronado National Forest, while I was reporting for the Arizona Daily Star (read more about my experiences embedding with crews in this piece for Powell’s Books).

Going through the training and spending a lot of time covering wildfires in the Southwest from 2002 to 2005 gave me the sense that safety is taken very seriously by fire managers and firefighters. But it was also easy to see how inherently dangerous the work is, especially once you add aircraft and fire engines to a dynamic environment that is often smoky, dark, and unfamiliar to the exhausted firefighters struggling to protect life and property.

Data sources

The National Interagency Fire Center maintains data on wildland firefighter fatalities on this page.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Wildland Firefighter Fatalities (5351 downloads )

- Download Notes: Wildland Firefighter Fatalities (5815 downloads )

- Download Data: Wildland Firefighter Fatalities (6025 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.