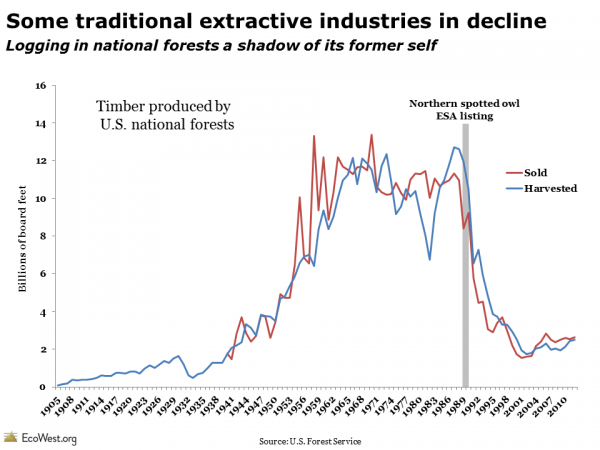

Logging on national forests, many of them located in the West, is a shadow of its former self. One of the clearest trends we found in our research was the decline in the timber harvest reported by the U.S. Forest Service, as shown in the graphic below (click to enlarge) and on our forestry dashboard.

Prior to creation of the Forest Service in 1905, the activity was largely unregulated in the West. After World War II, harvest rates increased significantly, but starting in the late 1970s, environmental regulations and international competition led to dramatic decreases in the amount of timber coming off public lands. Passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976 and restrictions related to the spotted owl in the 1990s led to major reductions in clear-cutting and other harmful practices.

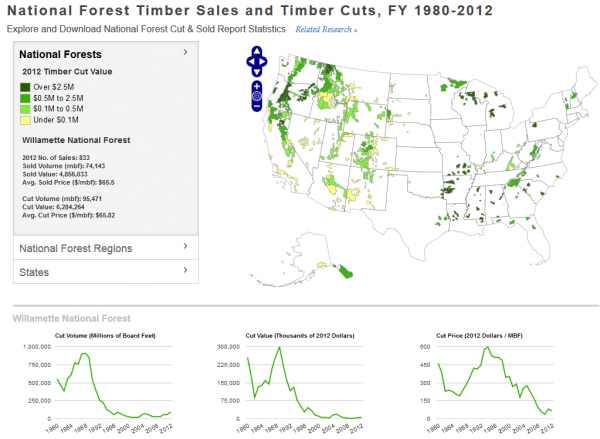

Interactive dashboard from Headwaters

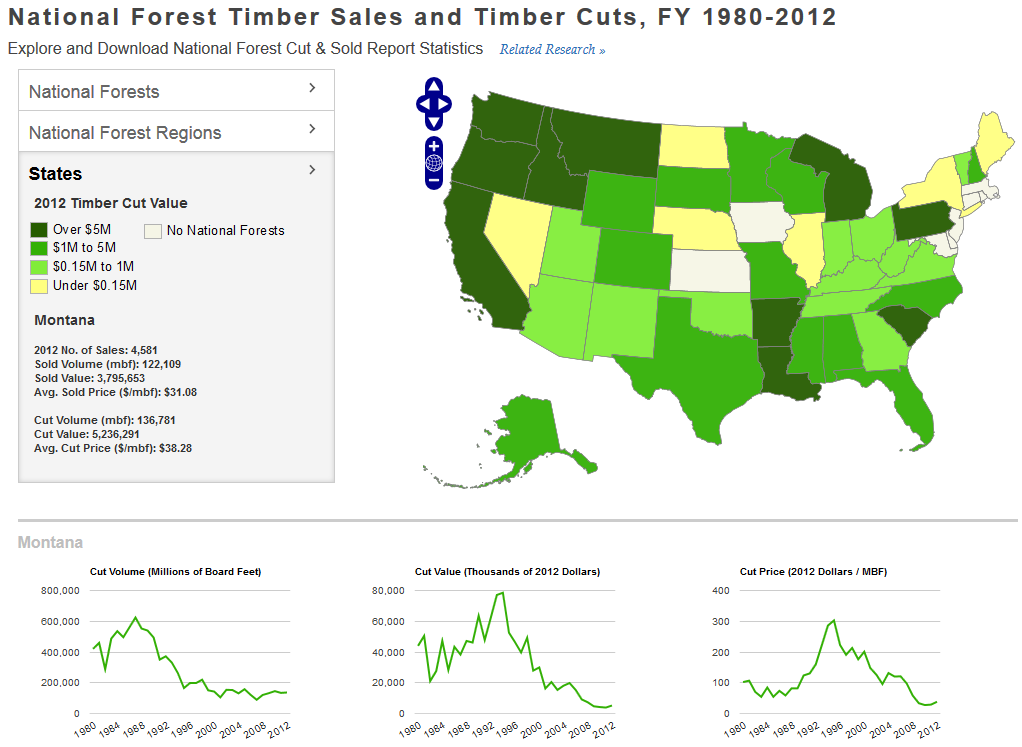

To learn more about public lands logging, check out the great dashboard that Headwaters Economics has developed. Although the data only goes back to 1980, the dashboard illustrates the timber harvest in each state, national forest, and U.S. Forest Service region.

In the screenshot below, I’ve highlighted Oregon’s Willamette National Forest. You can see a pretty stunning drop in logging starting around 1990, which is mirrored in other national forests in the region.

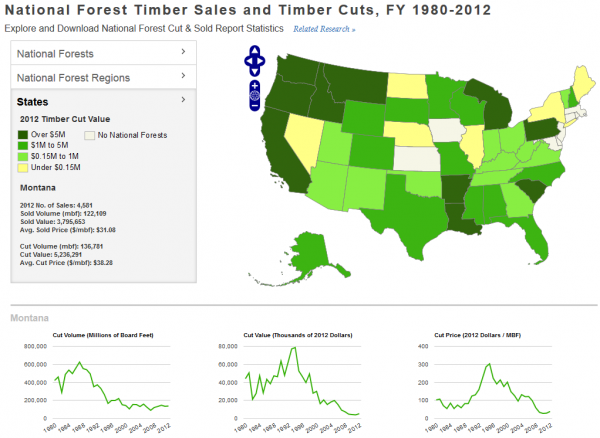

I was curious whether the timber harvest had also fallen as precipitously in places where there aren’t any spotted owls. The screenshot below highlights logging on national forests in Montana, which also declined, but not as sharply as in the West Coast states.

National forests aren’t the only places where logging takes place in the West. Especially along the Pacific Coast, there’s a ton of private and state land that’s actively logged. Some timber harvests also take place on tribal and BLM land. While national forests account for a big piece of the pie, it would be interesting to see whether the same trends are playing out on other lands in the West.

Data sources

The U.S. Forest Service provides historical data on harvests in this document and on this page. Headwaters Economics offers free downloads of the data in its interactive dashboard and provides more details on the data here.

Downloads

- Download Slide: National Forest Timber Harvest (5383 downloads )

- Download Data: National Forest Timber Harvest (5591 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.