Full disclosure: I love to ski and snowboard, so before reading further, you should know that I’m more of a passionate participant than neutral analyst of America’s snow sports industry.

But whether you’re a ski bum, X Games aspirant, or disinterested flatlander, it’s undeniable that a ton of money is changing hands when it comes to skiing, snowboarding, snowmobiling, and other sports dependent on snow.

In the 2012/2013 season, 8.2 million Americans alpine skied at least once, 7.4 million people snowboarded, and 3.3 million people cross-country skied, for a combined total of nearly 57 million skier-visits. Snowmobiling, which is especially popular in the Upper Midwest, generated more than 7 million visits in just three states combined: Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

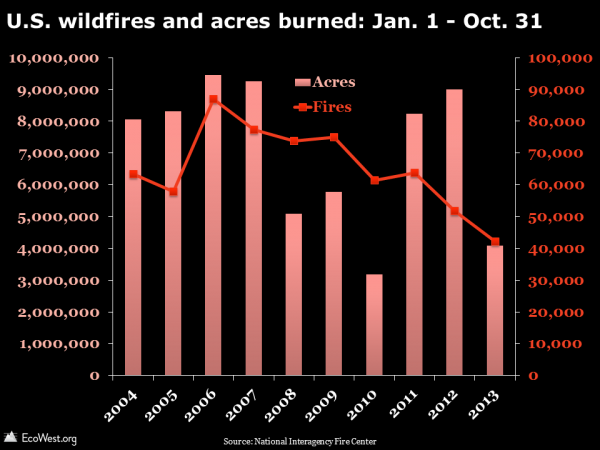

To cut to the chase: if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb, climate change is going to endanger America’s winter sports industry. Although a warming atmosphere can hold more water vapor, the precipitation will be more likely to fall as rain than snow, so even parts of the West that get wetter overall could see dramatic reductions in snowfall.

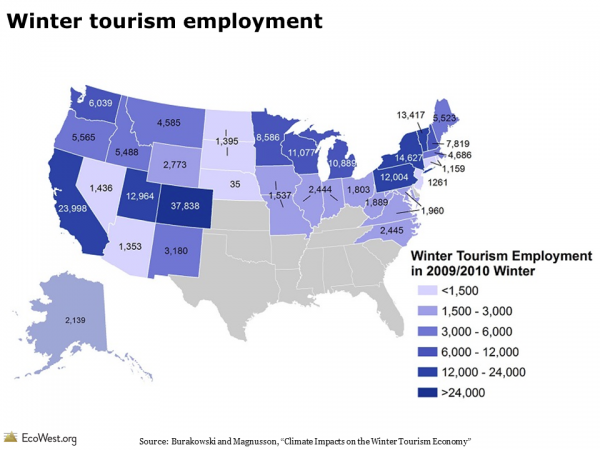

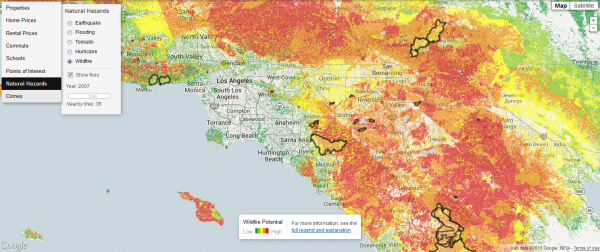

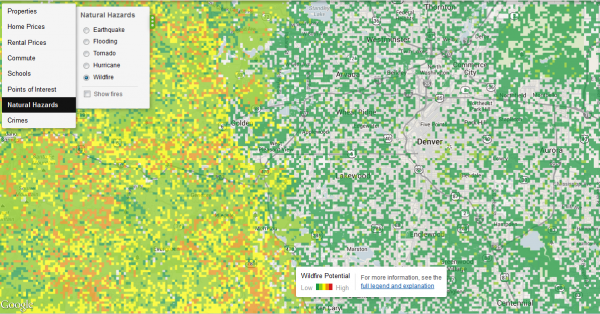

A diminished snowpack will jeopardize water supplies, increase wildfire risks, and transform entire ecosystems. Compared to these impacts, harm to ski bums and resorts may seem trivial, but in economic terms, low-snow years can devastate the tourism that some communities depend on. In the 2009/2010 season, U.S. winter sports trips generated nearly 212,000 jobs, labor income of $7 billion, and total economic value of $12.2 billion.

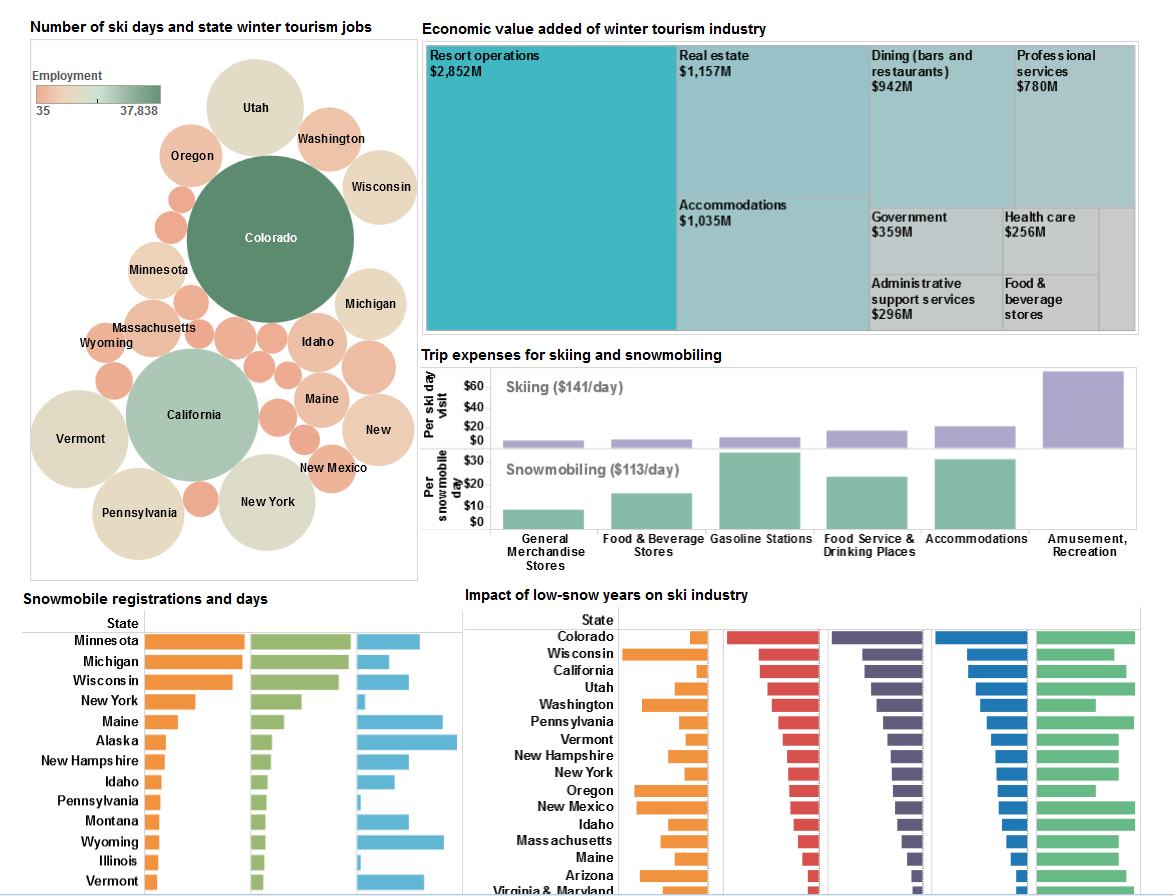

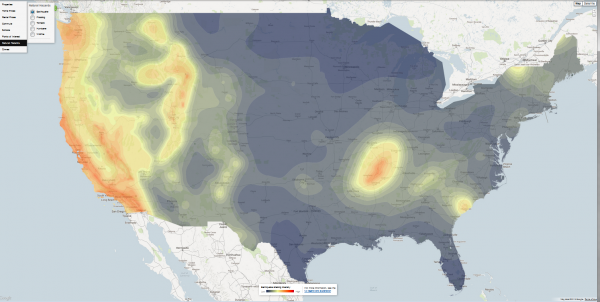

To illustrate what winter sports mean to the U.S. economy, I’ve created a dashboard on this page that visualizes data in a report from two researchers at the University of New Hampshire. Below is a screenshot (click to enlarge).

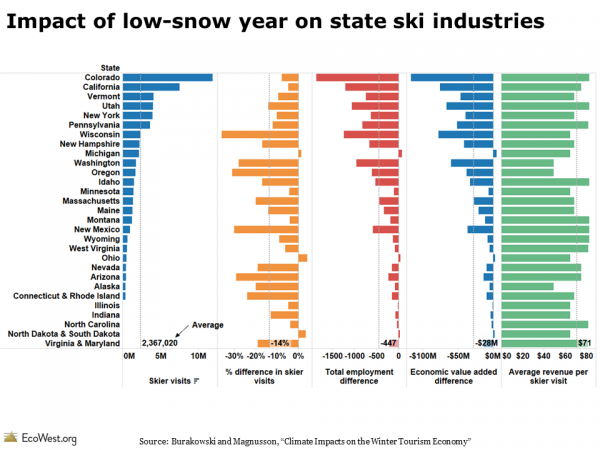

The Natural Resources Defense Council and Protect Our Winters, two advocacy groups, contracted with Elizabeth Burakowski and Matthew Magnusson to examine winter sports tourism in 38 states. The December 2012 report also estimates how much money each state lost, in jobs and economic value, in a low-snow year compared to a high-snow year.

In a future post, we’ll take a closer look at what the science is telling us about trends in the Western snowpack, but the authors of this report paint a bleak portrait of what’s to come under business-as-usual emissions scenarios:

Without intervention, winter temperatures are projected to warm an additional 4 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century, with subsequent decreases in snow cover area, snowfall, and shorter snow season. Snow depths could decline in the west by 25 to 100 percent. The length of the snow season in the northeast will be cut in half.

Yikes. Better seize those powder days while you can. I know I am.

Below is a summary of some visualizations from the dashboard, the original study, and other data sources.

Snow sports widespread

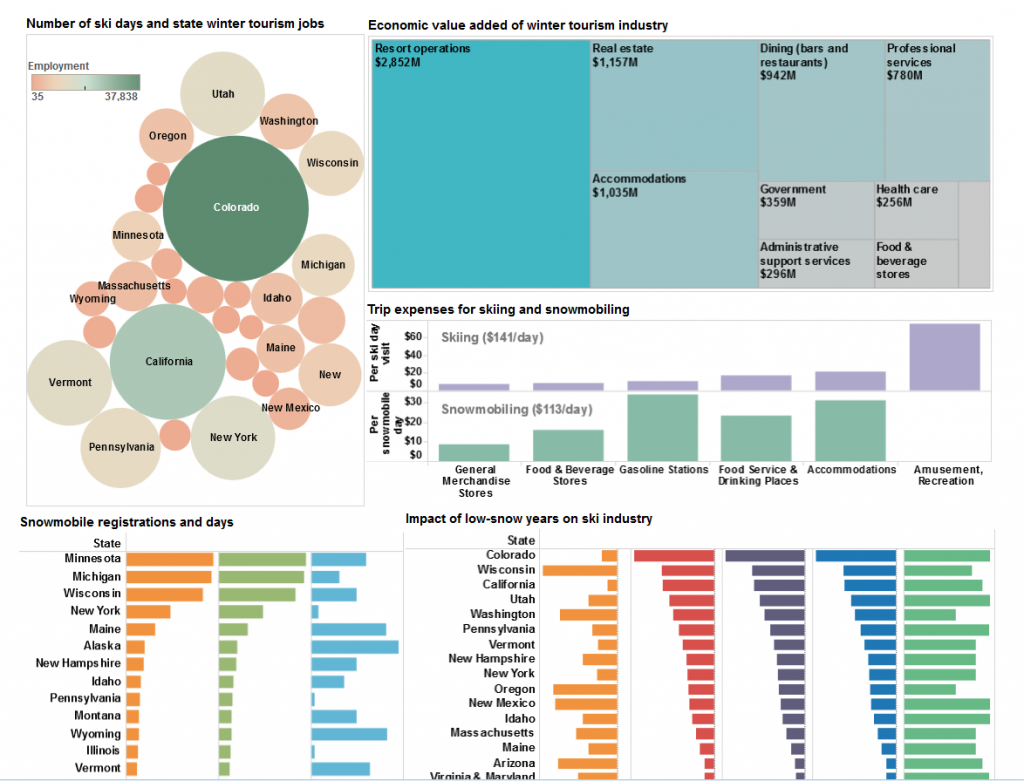

Here in Colorado, winter tourism is a major economic driver, and it’s no shock that we’re tops in the nation for skiing/snowboarding visits. Colorado accounted for one-fifth of ski and snowboarding visits, while one-eighth took place in California. What surprised me was that all but 12 of the 50 states have a winter sports economy (in reporting their findings, the authors did lump together some alpine powerhouses, such as Illinois and Indiana). If you factor in snowmobiling, the winter sports industry has an impressive geographic reach. In the graphic below, the circles are sized by the number of skiing/snowboarding visits and colored according to the number of snowmobiling visits.

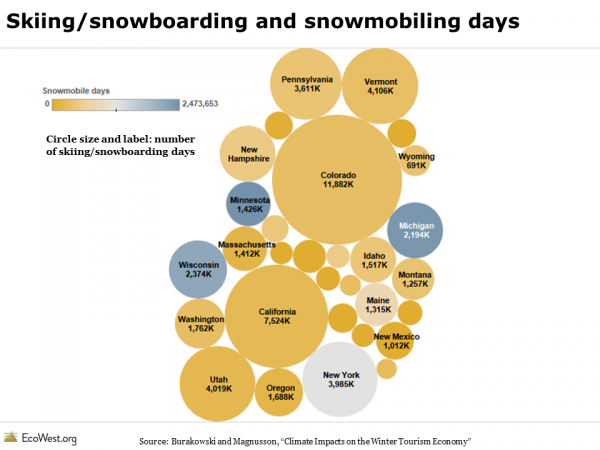

Data from another source, the National Ski Areas Association, confirms there’s plenty of skiing and snowboarding taking place outside of the West. I grew up skiing/skidding on the icy hills of Northern New Jersey, Vermont, and New Hampshire, and I can definitively state that the skiing out West is way better, but if you look at the number of visits to U.S. resorts, the Rockies and Pacific regions only make up about 55% of the total.

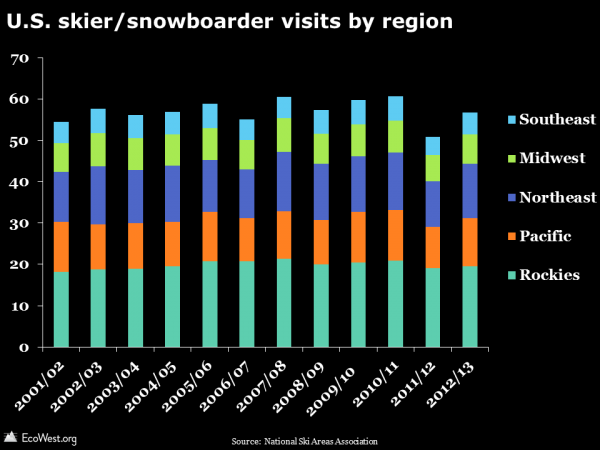

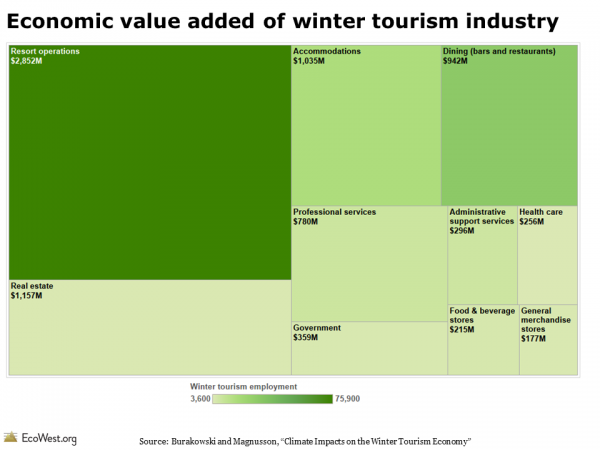

Billions at stake in winter tourism

It’s hard not to spend money while skiing and snowboarding, even if you live in Colorado. Before hitting the slopes, I’ll often fuel up my car at the gas station and fill my belly at my local greasy spoon. At the mountain, my annual ski pass helps pay for the parking attendants, lift operators, and ski patrol. Single-day lift ticket prices are north of $100 at some ski areas, which explains why “resort operations” is the biggest box in the graphic below.

Many ski areas have villages or minor cities at their bases with restaurants, shops, hotels, and spas. Whether it’s the glitterati buying up garish outfits or local yokels like me purchasing coffee for the drive home, money is circulating in the snow-based economy. In mid-February, at Denver International Airport, the wind-chill outside may be 10-below zero, but the baggage claim is a madhouse of travelers arriving from around the globe, ready to shell out big bucks.

Many ski areas have villages or minor cities at their bases with restaurants, shops, hotels, and spas. Whether it’s the glitterati buying up garish outfits or local yokels like me purchasing coffee for the drive home, money is circulating in the snow-based economy. In mid-February, at Denver International Airport, the wind-chill outside may be 10-below zero, but the baggage claim is a madhouse of travelers arriving from around the globe, ready to shell out big bucks.

In some cases, entire cities owe their existence to ski areas. Here in Colorado, communities such as Vail, Aspen, Breckenridge, and Telluride are synonymous with their ski mountains. These places see plenty of visitors in spring, summer, and fall. There’s actually some controversy about resorts getting too busy during the “off season.” Even so, winter sports are the magnet for many of these communities, snow is like manna from heaven, and the financial impact of winter sports extends far beyond chic destinations to the more humble places where planes land and tourists drive through. The map below shows that every Western state has more than 1,000 jobs connected to winter sports.

It’s important to remember that the data in our dashboard only tells part of the story. The data focuses on the local economic impact of skiing, snowboarding, and snowmobiling trips. Airline tickets are not included. Nor are the thousands of dollars that people spend on equipment and clothing. Last season, nearly $1.8 billion was spent at snow sports specialty stores on apparel, equipment, and accessories (in roughly equal proportions), according to SnowSports Industries America. Consumers spent about $750 million online on winter sports products.

Low-snow years harm industry

To gauge the impact of climate change, the University of New Hampshire researchers examined what happened to snow sports visits during low-snow years and then estimated the economic hit in the 38 states they studied. As shown below, some states appear to be more resilient than others. Colorado, California, and Utah suffered declines that were less than the national average, but other states, such as Washington, Oregon, and New Hampshire, saw skier visits fall even more than the national average.

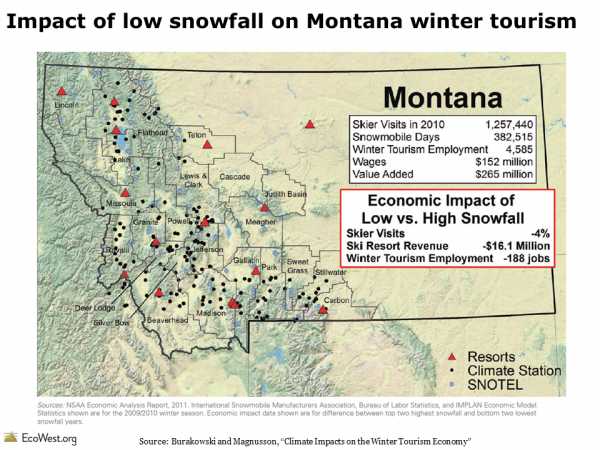

As an example, the graphic below shows that ski resorts in Montana lost $16 million in a low-snow year and winter tourism employment declined by 188 jobs due to the 4% decline in skier visits.

Industry faces questionable future

Skiing, snowboarding, and snowmobiling are certainly not without their environmental impacts. Fly west out of Denver on a clear day and you’ll see a lot of clear-cut strips marking the runs at the ski resorts. Below is a photo I snapped of Loveland Ski Area, where I wrote some of this post in between runs.

I’ve certainly done my share to cook the planet by driving into the mountains to ski and ride. A 114-mile round trip to Loveland from Denver causes my Subaru Forester to emit around 80 pounds of carbon-dioxide equivalent, according to the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Calculator.

But for me and millions of other Americans, playing in the snow is essential to our well-being. We’ll neglect family, friends, work, the health of the planet, and other concerns in order to get our white powder fix. Call it an addiction or healthy habit, snow sports are more than fun and games: they’re also an economic engine that climate change threatens to freeze.

Data sources

Climate Impacts on the Winter Tourism Economy, a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council and Protect Our Winters, is the source for data on jobs, economic value, and snow sports visits in the 38 states.

Data on skiing and snowboarding is also available from Snowsports Industries America and the National Ski Areas Association.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Winter Sports (10557 downloads )

- Download Notes: Winter Sports (10131 downloads )

- Download Data: Winter Sports (11310 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.