EcoWest recently had an opportunity to speak with Dee Frankfourth, Associate National Conservation Finance Director at The Trust for Public Land (TPL) and Eleanor Morris, Senior Policy Representative at The Nature Conservancy (TNC). We interviewed Frankfourth and Morris about trends they are observing in their conservation finance work to protect open space across the West.

Both TNC and TPL, along with local land trusts and other partners, secure public funding for conservation in the West and elsewhere through open space ballots and legislative initiatives.

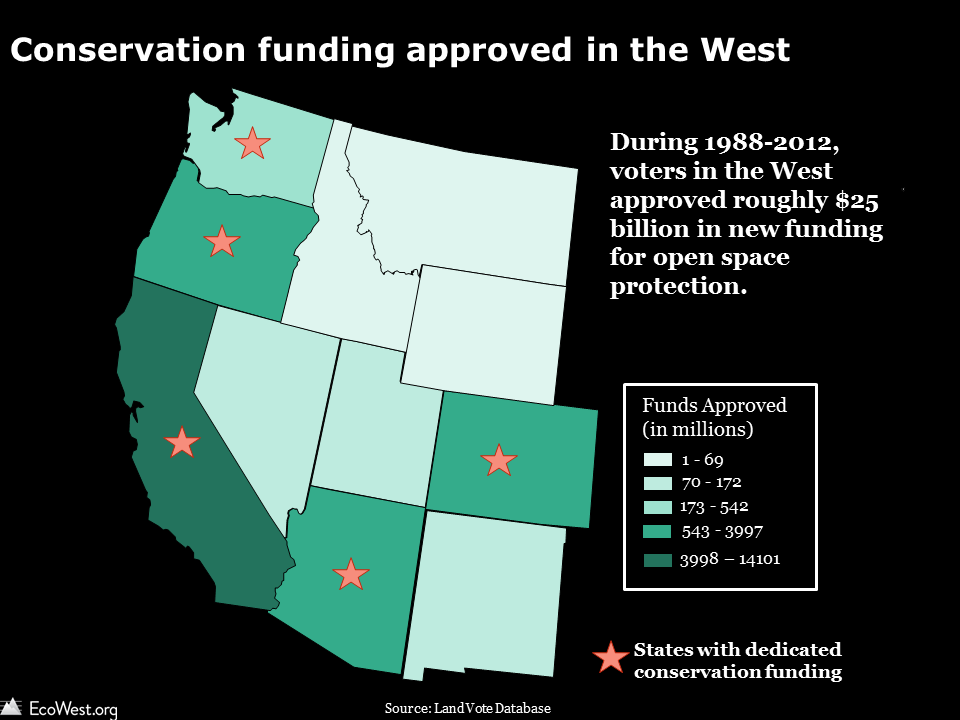

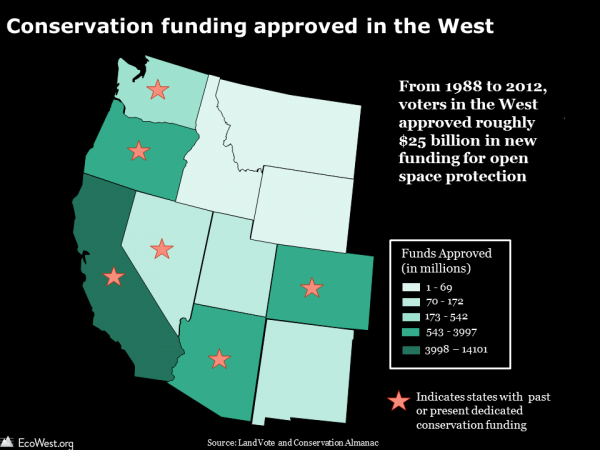

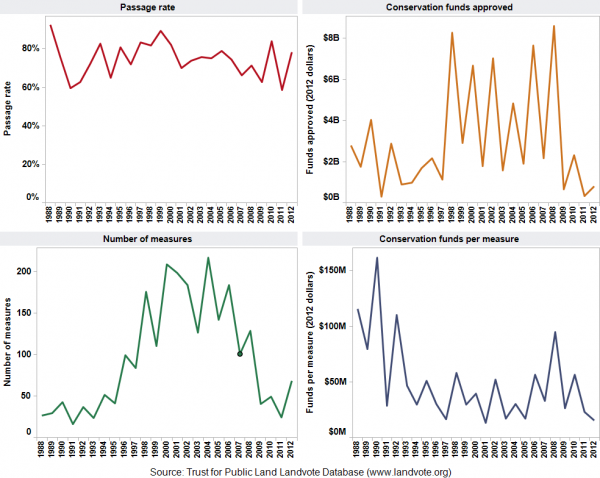

Conservation finance initiatives occur in two ways. First, the public can vote directly on a ballot measure to approve a new funding source (e.g., a bond, income tax, property tax, oil and gas revenues, or lottery proceeds). Second, legislatures can approve funding through a budget line item or general fund appropriation. You can learn more about conservation finance initiatives in this EcoWest post or on this dashboard (click the screen shot below to enlarge).

Below is an edited Q&A with Frankfourth and Morris.

Below is an edited Q&A with Frankfourth and Morris.

EcoWest: Can you highlight any conservation finance initiatives that have recently passed in the West?

Dee Frankfourth (TPL): Most measures in the West occurred in their primaries during May and August of this year, including:

- Blaine County, Idaho: This county, located near Sun Valley, passed a $3.5 million property tax to reconstruct the 20-mile Wood River recreational trail. This is actually quite a significant amount for a rural county, and it passed overwhelmingly, with 83 percent approval.

- Portland, Oregon: With 54% of the vote, the metro area of Portland that includes parts of three counties passed a $50 million property tax for stewardship of lands acquired during two previous bond measures, and to fund other open space acquisitions.

- King County, Washington: This county surrounding Seattle, the 17th largest in the nation, passed by 70% a six-year property tax that will start at $60 million in the first year and increase annually. The measure will help keep county parks and trails in good condition and also provide funding to protect new open spaces.

The graphic below, based on TPL’s LandVote database, shows that Western voters approved some $25 billion in conservation funding from 1988 to 2012.

EcoWest: Given that water is arguably the most precious natural resource in the West, have you observed a link between the public’s willingness to conserve land and their motivation to protect water resources?

Eleanor Morris (TNC): I’m constantly impressed that this connection is instantaneous for Americans. It’s a no-brainer—they intuitively understand, “If I protect this piece of land, then I protect my drinking water.” And this is not a new trend necessarily. Water has always been a huge driving force in conservation finance in the West. It consistently ranks as a top reason in polls as to why people are motivated to pay for land protection

EcoWest: Federal funding programs play a key role in making conservation finance initiatives possible. Have recent financial challenges in D.C. presented any threats to these funding sources?

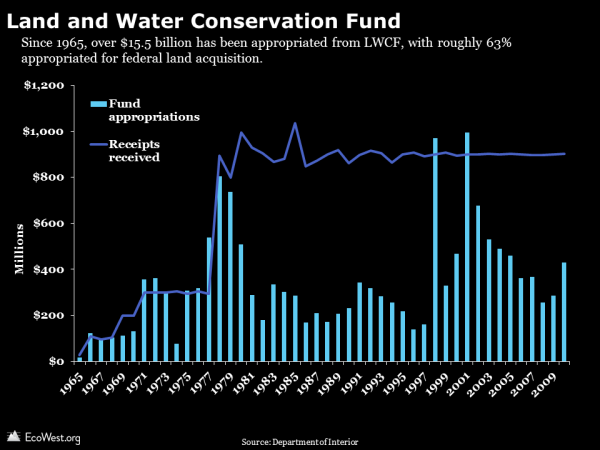

Dee Frankfourth (TPL): The trendline in general for federal funding is definitely of concern. The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) is slated to end in 2015, since it was initially designed as a 50-year dedicated funding source. TPL and our partners are currently working to build allies in Congress to ensure leadership for either a renewal of this fund or a new source that supplants it. The federal government provides an important value proposition to states: “We’ll give you [the state] 50 percent of funding if you put in the other half for a conservation project.”

The graphic below summarizes LWCF appropriations and receipts. Learn more about how the LWCF works in this report from the Congressional Research Service.

EcoWest: Eleanor, can you tell us about the Montana Legacy Project, the nation’s largest private conservation purchase? Are there any key lessons learned from TNC’s efforts to protect those 310,000 acres?

Eleanor Morris (TNC): Yes, this project had an innovative and unprecedented funding package from the federal government, Montana state government, and private sources. On-the-ground support from the public was another important feature that made this deal possible. TNC and our partners worked in counties that were already 80 to 90 percent public land. It took concerted effort to work with communities in these counties and discuss how they envision their future land use.

EcoWest: Have you observed a trend of “conservation envy” in your work – where one county creates a dedicated source of conservation funding, and an adjacent county seeks to follow suit?

Dee Frankfourth (TPL): Yes, there is currently a county in southeastern Washington undertaking the process to create a dedicated pot of conservation funding. This is a great example of a county, in a very conservative part of the state, looking next door at Spokane, seeing how they are protecting their parks, open space, and natural areas with a dedicated fund created 20 years ago, and thinking how it should do the same. After TPL presented to elected officials in the county last March, we performed feasibility research this summer and found that it would cost $11 per household annually (less than $1 per month) to create a dedicated conservation funding source. The next step is to conduct a public opinion survey of registered voters to see if there is sufficient support to warrant moving ahead with a ballot measure.

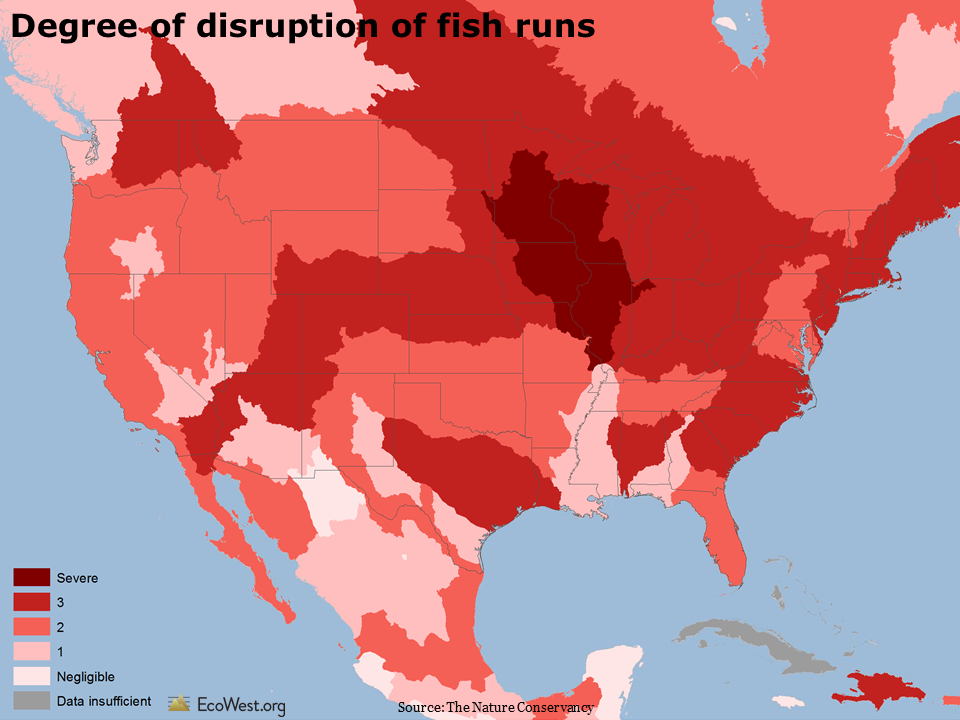

EcoWest: How might growing concern about fire and drought as threats to local water supplies influence TNC’s work going forward?

Eleanor Morris (TNC): Last year, the City of Flagstaff, Arizona approved a $10 million bond to protect nearly 15,000 acres of forest land outside the city’s limits. This was an important measure showing that voters were willing to tax themselves to protect national forest land for watershed services. TNC is now developing strategies to look at whole watersheds, whole ecosystems, whole landscapes. We’re looking at the entire state of Oregon, and the bulk of the state of New Mexico. The aim is to protect lands beyond the reach of one individual city, in order to safeguard all water resources that might be connected to an area’s water supply.

Editor’s note: The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, which supports EcoWest.org, has funded TPL, TNC, and the Montana Legacy Project, but the foundation does not exert editorial control over this website.

Downloads

- Download Slides: Conservation Finance (5312 downloads )

- Download Notes: Conservation Finance (6486 downloads )

EcoWest’s mission is to analyze, visualize, and share data on environmental trends in the North American West. Please subscribe to our RSS feed, opt-in for email updates, follow us on Twitter, or like us on Facebook.